The post Throwback Thursday: It’s Judgement’s Day In The Spruce Meadows International appeared first on The Chronicle of the Horse.

]]>In recognition of the 50th edition of the Spruce Meadows ‘Masters’ tournament, taking place this week in Calgary, Alberta, and culminating with the record prize-money $5 Million CPKC ‘International’ Grand Prix (approximately $3.62 million USD), this Throwback Thursday we’re looking back at 2005, when Judgement, ridden by Beezie Madden, became the first North American-bred horse to win the event. This article was first published Oct. 27, 2005.

When Beezie Madden galloped into the ring as the second competitor in the two-horse jump-off of the $843,844 CN International, she knew what she needed to do. Nick Skelton and Arko III had jumped clear, but he left a window of opportunity.

With cool confidence, she shoved the window open and guided Judgement to perfect, forward distances that shaved more than 2 seconds off Skelton’s time with Arko.

After she crossed the finish line and looked up at the clock tower scoreboard, a huge grin ensued and she pumped the air with her fist before enthusiastically patting her black stallion while she cantered to the out-gate.

Their perfect performance over three demanding rounds left the pair as victors in the world’s richest grand prix, held as the culminating event of the Spruce Meadows Masters, Sept. 7-11 in Calgary, Alberta.

Madden, 41, of Cazenovia, New York, joins an elite group—she’s the first woman and first American to win this prestigious class since 1997, when Leslie Howard and S’Blieft were victorious. George Morris, who won in 1988 with Rio, and Norman Dello Joio, the winner in 1983 riding I Love You, are the only other U.S. riders to have won the class.

Judgement (Consul—Faletta, Akteur), owned and bred by Iron Spring Farm of Coatesville, Pennsylvania, is also the first U.S.-bred horse to take the title. Of the 47 starters, Judgement was also the only U.S.-bred horse in the field.

“He felt better than ever,” said Madden of her 14-year-old Dutch Warmblood. “Right from the first jumps in the schooling area he felt fantastic. He did one class during the week and jumped great. He was just waiting for an opportunity.”

The Canadians had a lot to cheer for. Mario Deslauriers incurred 1 time fault over the two rounds to place third riding Paradigm, and Eric Lamaze had a heartbreaking rail at the last fence in round 2 to place fifth with Hickstead.

Germany’s Ludger Beerbaum, who won the CN International in 2002, placed fourth riding L’Espoir Z, a 9-year-old, Zangersheide gelding (by Landwind II). One time fault was all that kept Beerbaum from the jump-off.

A Rewarding Decision

After Saturday’s torrential rains, which resulted in the BMO Nations Cup being canceled following the first of two rounds (see sidebar), the footing in the International Ring was still soggy on Sunday. After four days of relentless rain and drizzle, the weather cleared on Sunday, and the sun peeked through the clouds by 11 a.m. The riders, coaches and chefs d’equipe spent lots of time walking the course and examining the footing, deciding whether or not to start their horses.

U.S. riders Dello Joio and Jeff Campf scratched Glasgow and Lady-D, respectively. Madden also made a last-minute substitution. She had originally nominated Authentic, her Athens Olympics gold-medal mount whom she’d ridden in the previous day’s Nations Cup, but changed her mind when the conditions hadn’t greatly improved.

Course designer Leopoldo Palacios carefully considered the circumstances and set his fences where the footing was firmest. Therefore, most of the jumps were set at the edges of the ring where the drainage was best.

“I made three courses since last night,” joked Palacios on Sunday afternoon.

The footing held up admirably, and the organizers took every effort to keep conditions as optimal as possible. After the 25th of 47 horses started, there was a 20-minute break to work the footing and adjust some fences.

Cayce Harrison, daughter of CN CEO Hunter Harrison, was the only rider to hit the wet ground during the class. Her horse, Coeur, threw a shoe after the first fence but jumped gamely until the triple combination. Then he tried to pat the ground at the A element, a triple bar, but slipped and swam through the fence. Cayce fell and slid underneath the B element, but the gray carefully jumped over her and the fence and continued through and over the C element.

She walked out of the ring with her father by her side, and it was announced that she suffered no serious injury.

Palacios’ first-round course received rave reviews as 13 competitors jumped clear rounds. The fastest 12 qualified for the second round, including three U.S. riders: Lauren Hough aboard Clasiko, McLain Ward on Sapphire, and Madden.

For the second round, Palacios said he raised the jumps to “as big as any CN International class,” and a tight time allowed added to the difficulty.

Beerbaum and Deslauriers each negotiated the second round clean, but 1 time fault kept them out of the jump-off.

Ward and Sapphire looked as though they were going to join the jump-off until a rail at the second-to-last fence dropped to the ground. He placed seventh. Hough and Clasiko had two rails, including one at the challenging triple combination of liverpools, to finish 11th.

In the end, it was a face-off between an American rider and a British rider. The best over the eight-effort jump-off would take home the winner’s share of $274,315. Skelton and Arko III, an 11-year-old Oldenburg stallion (Argentinus—Unika, Beach Boy), went first and jumped clean in 48.02 seconds over the winding course, putting some pressure on Madden.

“But in that situation, whatever I did, Beezie would do better,” said Skelton simply. “I went as quick as I could go without leaving anything in danger.”

Madden and Judgement left out strides here and there, and his long galloping stride carried them to a time of 46.04 seconds, good enough for all the spoils, including a $41,631 bonus for winning two CN Precision Series grand prix classes during the 2005 season.

“It was just a fantastic day,” said Madden, smiling. “I’m lucky to have the horses and owners I have. There are so many people involved, and it’s incredible what we have. This was quite a climax.”

For Deslauriers, third place was a huge accomplishment. His horse, an 11-year-old Belgian Warmblood (by Nabab de Reve), was competing in 1.40-meter classes this spring and only began the larger grand prix classes over the summer. This was Deslauriers’ fifth grand prix with the chestnut gelding, a former mount of Canadian grand prix rider Mark Laskin.

“This was a huge step up here,” said Deslauriers, 40, of Bromont, Quebec. “The course was difficult, but he handled it beautifully.”

The post Throwback Thursday: It’s Judgement’s Day In The Spruce Meadows International appeared first on The Chronicle of the Horse.

]]>The post Throwback Thursday: Bold Minstrel Was The Horse Of The 20th Century appeared first on The Chronicle of the Horse.

]]>Born in 1952 in Camargo, Ohio, Bold Minstrel was by Thoroughbred stallion Bold And Bad out of Wallise Simpson, who was the result of a test breeding of an unknown mare to a young Royal Minstrel. William “Billy” Haggard III purchased Bold Minstrel as a 5-year-old.

While Haggard never had any formal training, he competed at the highest levels of sport. From steeplechasing to show hunters to eventing, Haggard proved himself over and over again as one of the top riders of his time.

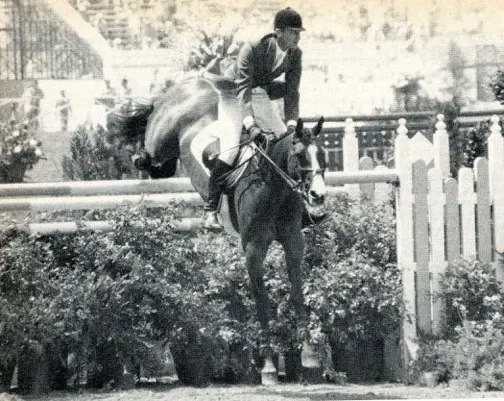

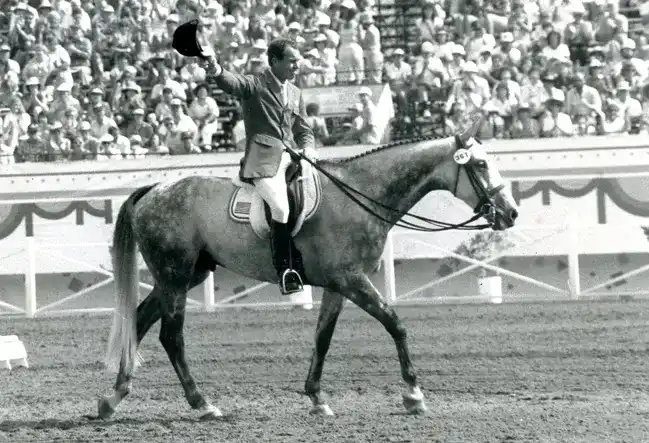

William Haggard and Bold Minstrel.

Topping out at 16.3 hands, the stunning gray was such an easy keeper that he was affectionately called “Fatty.” Bold Minstrel’s career actually began in the hunter ring, and his stunning looks and lovely jump garnered him dozens of ribbons in the conformation divisions across the country, including a reserve championship at the National Horse Show (New York). Eventually, though, Haggard switched his focus to eventing.

In 1959, Haggard and Bold Minstrel tackled the Pan American Games in Chicago, Illinois, and helped the U.S. team win the silver medal in addition to placing ninth individually. Four years later, they were sixth individually in São Paulo, Brazil, and clinched the team gold. Between those two Games, Haggard still campaigned Bold Minstrel in the hunter ring.

William Haggard and Bold Minstrel showing in the hunters at Devon. The pair competed successfully in the hunters in addition to eventing. Jimmy Ellis Photo

While it seemed like the pair would be a shoo-in for the Olympic Games in Tokyo the following year, the selectors did not include them on the team. However, when J. Michael Plumb’s mount, Markham, had to be euthanized on the flight over, Haggard loaned Bold Minstrel to the veteran rider.

“Michael Plumb, as can be imagined, was at a tremendous disadvantage having to compete in the Olympic Games after only riding the horse for two weeks before hand,” wrote teammate Michael Page in the Nov. 20, 1964, edition of The Chronicle of the Horse. “However, from the excellent dressage ride on the first day, to the ‘must’ clear round to protect the medal on the last day over a trappy jumping course, Plumb and Bold Minstrel never once shook the confidence placed in them.”

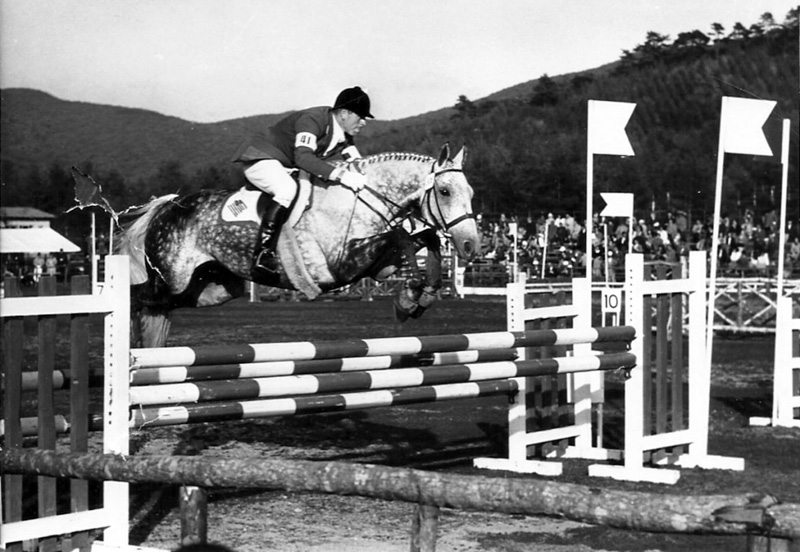

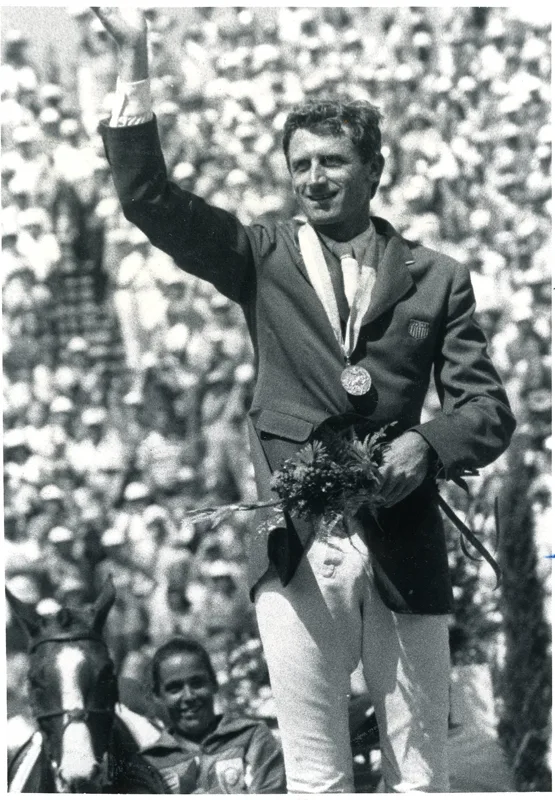

Michael Plumb and Bold Minstrel in the show jumping at the 1964 Olympic Games.

Since Bold Minstrel was only 12 after his first Olympic Games, where he helped the team earn silver, Haggard decided to continue to campaign him. However, as the horse had already reached the highest levels of two sports, he loaned him to Bill Steinkraus.

Steinkraus rode the gray gelding in numerous international show jumping events between 1964 and Bold Minstrel’s retirement in 1970. They won more than a dozen major competitions, including the Grand Prix of Cologne (Germany). In 1967, they also set two puissance records at the fall indoor shows, jumping 7’3” at the National Horse Show.

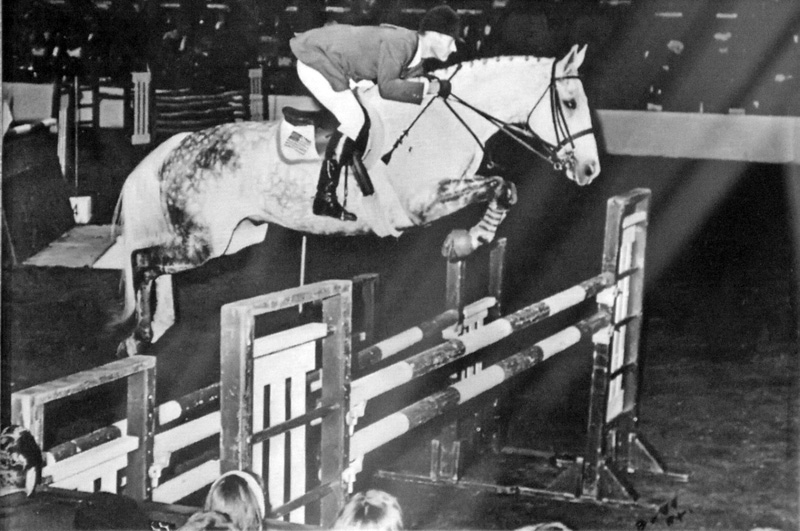

Bill Steinkraus and Bold Minstrel.

“It takes something special to make me wear a white tie and tails to a horse show, but the old Garden was special,” wrote Jimmy Wofford in the April 2008 issue of Practical Horseman. “I was willing to dress up like the Phantom of the Opera to watch quality show jumping. It was even more special when Bill Steinkraus came out of the corner next to me on his way to a 6-foot 7-inch puissance wall. With his uncanny eye for a distance, Bill saw a steady seven strides to a deep distance. This is just what you want when you are about to jump a big puissance wall. Unfortunately, Fatty saw a going six, grabbed the bit and opened up his stride. The book will tell you that you can’t jump that big a fence from that big a stride, but Fatty left it standing, much to Bill’s relief.”

Bill Steinkaus rode Bold Minstrel in the 1967 Pan American Games in show jumping, where the gelding won yet another team silver medal. They also set several puissance records in that same year. Budd Photo

Bold Minstrel competed in his third Pan American Games in show jumping in Winnipeg, Manitoba, that same year and, again, earned the team silver. That medal solidified Bold Minstrel’s epic career, making him the only horse to have medals in three Pan American Games and one Olympic Games in two disciplines.

Bold Minstrel continued to compete well into his late teens and eventually retired in 1970 at 18 years old. That year, he won three times at Lucerne (Switzerland) and won the Democrat Challenge Trophy at his old stomping grounds, the National Horse Show. After he retired from competition, Haggard took him home to his farm and foxhunted him.

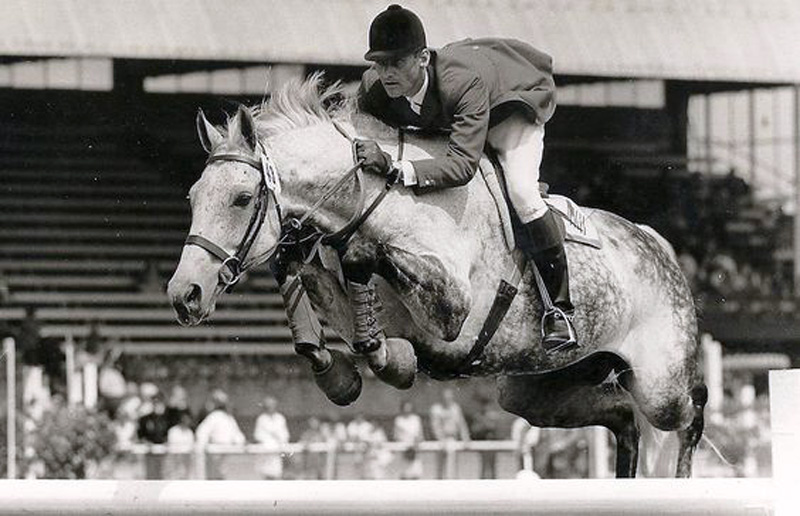

Bill Steinkraus showing Bold Minstrel.

“This gray horse gets my vote as the greatest horse of the 20th century,” wrote Dennis Glaccum in the Dec. 24, 1999, issue of the Chronicle, where Bold Minstrel was named one of the most influential horses of the century. “He stands heads and tails above any other horse I have observed in my lifetime.”

In 2011, COTH writer Coree Reuter embarked on a quest into the attic at the Chronicle’s office. While it’s occasionally a journey that requires a head lamp, GPS unit and dust mask, nearly 75 years of the equine industry is documented in the old issues and photographs that live above the offices, and Coree was determined to unearth the great stories of the past. Inspired by the saying: “History was written on the back of a horse,” she hoped to demystify the legends, find new ones and honor the horses who have changed the scope of everyday life. This article was originally published Feb. 2, 2011.

The post Throwback Thursday: Bold Minstrel Was The Horse Of The 20th Century appeared first on The Chronicle of the Horse.

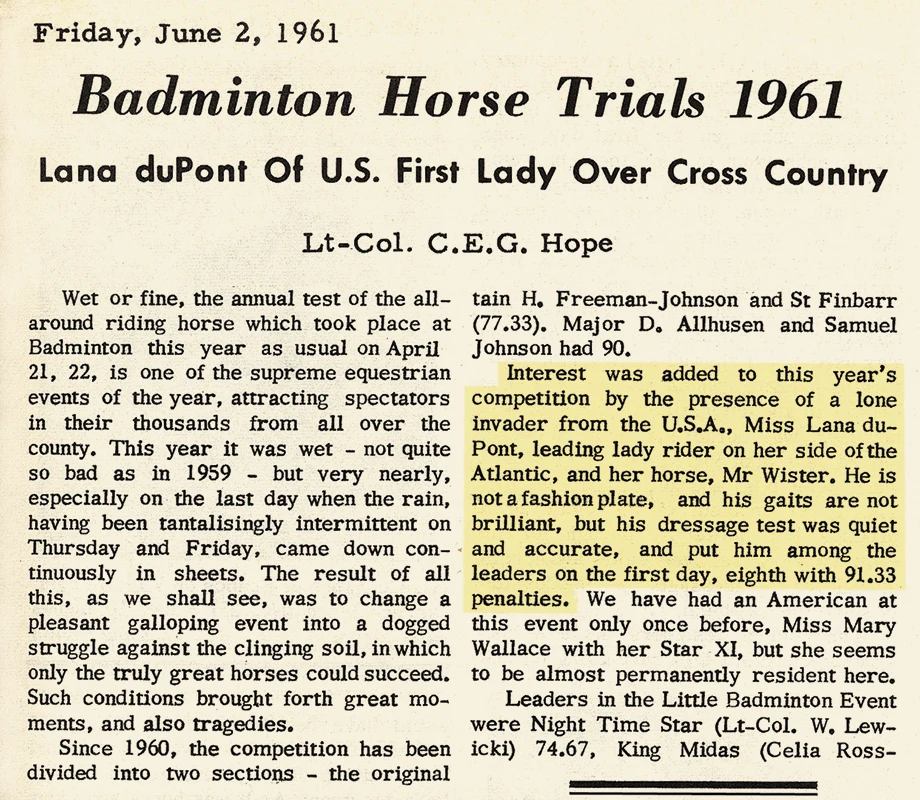

]]>The post Throwback Thursday: Lana duPont ‘Did It Because She Loved It’ appeared first on The Chronicle of the Horse.

]]>In 1964, 25-year-old Lana duPont Wright became the first woman to compete in eventing at the Olympic Games, winning team silver and immediately etching her name in the annals of equestrian sport as a trailblazer. But she never saw herself that way, say the people who knew her best.

Instead of making the trek to the Tokyo Games focused on breaking a glass ceiling, Wright’s Olympic appearance was simply the natural outcome of her lifelong passion for horses and horsemanship—a passion she pursued with a level of drive and enthusiasm that raised the game of everyone around her.

“She had no clue what she was doing for the future,” said fellow Olympian Donnan Sharp, 86, of Unionville, Pennsylvania, one of Wright’s best friends since childhood. “She did it because she loved it, and she could do it. The thought of ‘look what she did for women,’ she had no inkling of.”

In fact, eventing was just one facet of Wright’s storied career in horse sport. She was also a lifelong foxhunter, and she went on to represent the U.S. on international teams in both combined driving and endurance. A strong advocate for U.S. Pony Clubs, she hosted the Middletown Pony Club at her Unicorn Farm in Maryland, and she provided mounts for countless children over the years.

As an organizer, Wright was responsible for coordinating, designing and building for equestrian competitions ranging from local paper chases to horse trials to international combined driving and endurance competitions, often on her own farm. Wright was somewhat famously unassuming, humble and reticent to talk about herself, but when she died in April at age 85, she left behind a legacy of excellence and service to equestrian sport that continues to benefit future generations and inspire those who knew her.

“She was such a big deal,” said Diane Trefry, 75, who was Wright’s team manager for over 50 years. “She was such a gentle professional with her horses. If you watched her ride or drive, she was very precise, and kind to them, but she also took no nonsense. She never bought something that was made. Part of her pleasure and joy was to make a horse herself. She was hands-on.

“Every horse should have a job, in her book, and every kid who wanted a pony should have an opportunity to ride a pony,” she continued. “She took van loads of ponies to Vermont in the summer, and the Pony Club kids could go and do an event. Many kids were the recipients of that, and she made so much happen for Pony Club, through gifting her own horses and giving lessons. She was just very generous. What she had, and what knowledge she had, she shared.”

From Foxhunting To The World Stage

Wright and Sharp lived near each other as children and soon bonded over their mutual love for ponies and riding. The pair spent hours hacking out in the countryside together, unencumbered by rules, adults, or real-life responsibilities. Both young women loved to foxhunt, first with the local Vicmead Hunt Club in Delaware, then later with many of the prestigious Virginia hunts, including Orange County, Piedmont, Old Dominion and Blue Ridge.

Foxhunting remained a lifelong passion for Wright, and the skills both women gained in the hunt field set them up for their early encounters with the sport of eventing as young adults. It was Wright who first learned about the sport—then new to civilians—as a preteen while studying at Oldfields School, an all-girls boarding school in Maryland.

“The coach who was there at the time had just been exposed to eventing, so he got all the Oldfields riding people interested,” said Sharp. “Lana got involved, and for the next three years, just kind of played around with it at school.”

When the girls graduated in the late 1950s, both skipped college in favor of pursuing their equestrian goals. By then, eventing had caught their interest. Riding across country came naturally, thanks to their years in the hunt field, as did show jumping—but the dressage phase proved more problematic.

“Neither one of us had a clue,” says Sharp. “We’d read a few books, but we didn’t really know what the heck it was all about. That’s when we became involved with Richard Wätjen.”

Wätjen, a highly accomplished German dressage trainer who had previously trained and taught at the Spanish Riding School in Vienna, immigrated to the U.S. in the late 1950s to work with Karen McIntosh at her family’s Sunnyfield Farm in Bedford, New York. At the time, there were few coaches specializing in dressage, making someone with Wätjen’s skill and experience invaluable.

“We found Wätjen was the guru to go to for this peculiar dressage event,” said Sharp with a chuckle. “We took a couple of foxhunters up there, in hopes he could teach us something.”

It wasn’t long before the foxhunters were back in their stalls, and Wright and Sharp were learning dressage basics on trained schoolmasters. But Wätjen quickly discerned that both women were truly interested in learning and had bigger goals than simply riding circles at home. When Sharp and Wright were invited to train with the U.S. Equestrian Team in Gladstone, New Jersey, in the early 1960s, Wätjen accepted the women’s invitation to join them. It was a move that proved fortuitous to the success of riders on the nascent U.S. eventing and dressage teams, many of whom worked with Wätjen until his death in 1966.

Meanwhile, in 1958, the friends hosted the first Vicmead Horse Trials in Delaware. It offered just two levels, novice (now preliminary) and advanced, and it attracted only eight entries. The competition was significant not only because it was the first of many that Wright would go on to host and organize in her career, but also because in its second year, the Canadian squad entered it as a final prep for the 1959 Pan American Games in Chicago.

“We really beefed it up,” Sharp recalled with a laugh. “Wätjen even came down to judge dressage.”

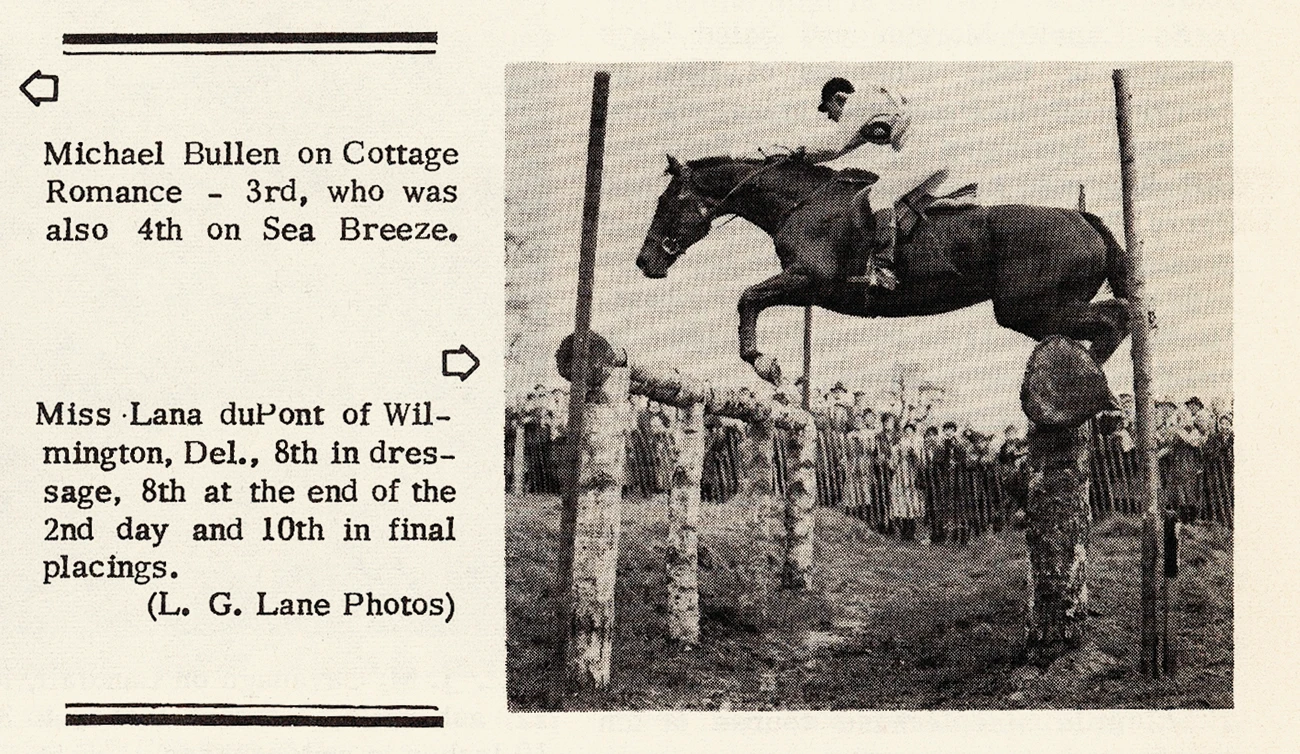

Seeing some of the best amateurs in the sport compete at her own event was the first of several fortuitous occurrences that helped set Wright up for an Olympic bid just four years later. She and Sharp took great inspiration from spectating at both the Chicago Pan Ams and the 1960 Olympics in Rome; along the way, they also attended a meeting in Illinois that would result in the creation of the U.S. Combined Training Association (now the U.S. Eventing Association). And around the same time, a special partnership began to solidify between Wright and a somewhat quirky homebred Thoroughbred of her mother’s, Mr. Wister.

Though bred for the track, “Wister” wanted no part of that lifestyle. He dumped all his jockeys; he often refused to enter the starting gate. Though he did eventually run a handful of times, it was with modest success. Wright took over the ride when the rangy gelding was 3 or 4 years old.

“I’m not sure what she saw in him, except he was a gorgeous, big-boned Thoroughbred,” said Sharp. “She had quite a tussle with him. It took her a summer to be able to stay on and get him to be manageable. But he caught on quickly that this might be OK, and there was obviously a great rapport between the two of them. He went on to do anything for her, which in itself is a pretty good story, having seen him from day one.”

Wister and Wright trained for several years at Gladstone, then in 1963, went to England to train there as a final preparation before attempting the Badminton Horse Trials, where she placed 10th. Sharp, who married U.S. eventing team stalwart Mike Plumb in 1964, remembers that during their time with the team, no one thought them less capable for being women.

“No one was really thinking, ‘Oh, girls can’t do this,’ because there were girls out there competing,” said Sharp. “The boys had gotten used to us girls competing against them at the national level, and they were fine with it. It’s just the rules [for the Olympics] didn’t allow it.”

By the time the rules did change, before the 1964 Tokyo Olympic Games, Wätjen had convinced Sharp to focus exclusively on dressage, and she went on to help the U.S. win team silver at the 1967 Pan Ams (Winnipeg) and rode on the team at the 1968 Mexico City Olympics. But Wright, bolstered by her success with Wister, stuck with eventing.

“Lana hung in with the eventing because she had this awesome horse,” said Sharp. “She battled it out, not really aiming for the Olympics but aiming to do the best she could do at all the events. So she eventually out-rode and out-performed everybody, and when the rules changed, they took her on. We didn’t have a very strong group in those days, but the horse—and Lana—legitimately made the cut. She may have been the only female, but she wasn’t an oddity, because she could do the job.”

On endurance day at the 1964 Olympics, it poured and poured, and the horses churned the footing into a deep muck. By the time Wister and Wright headed out on cross-country, conditions were poor, and the pair fell not once but twice on course. Unbeknownst to anyone, Wister had broken his jaw in the first fall, but he seemed game to continue. Sharp happened to be standing nearby when the pair fell the first time, and she gave her friend a leg up back into the saddle.

“She was a mess, and can you imagine, a horse with a broken jaw, and went on anyway,” says Sharp. “Obviously, we can’t get away with that anymore. But she got around.”

In an oft repeated quote, Wright recalled her Olympic cross-country experience as follows (here from the “U.S. Team Book of Riding”):

“When we finished, we were a collection of bruises, broken bones, and mud. Anyway, we proved that a woman could get around an Olympic cross-country course, and nobody could have said that we looked feminine at the finish.”

“No one was really thinking, ‘Oh, girls can’t do this,’ because there were girls out there competing. The boys had gotten used to us girls competing against them at the national level, and they were fine with it. It’s just the rules [for the Olympics] didn’t allow it.”

Donnan Sharp

Maybe not, but that finish nonetheless broke down a door that other women were waiting impatiently behind.

“She was our friend, and she had made it to the top, and we were thrilled to be part of it,” said Sharp of Wright making eventing history. “But England had all these girls who should have been on their team, and they were banging on the door. It was an evolution, I think, more than Lana having done it. [Women in Olympic eventing] had to happen, and good for the U.S., to let it happen.”

Those Olympics, where Wright and her teammates earned the silver medal, were essentially her swan song at the elite level of eventing. Not long after, she left the team, married and started a family. But she was far from done with horses.

Driving Into The Future

Trefry first met Wright when she was working for her mother, the acclaimed Thoroughbred breeder Allaire duPont, at Woodstock Farm in Maryland. It wasn’t long before Trefry was giving riding lessons to Wright’s young daughters, and soon, she moved over to work at Wright’s Unicorn Farm—contiguous to Woodstock—full time. She stayed for five decades.

“She became more than an employer to me,” said Trefry. “She was my friend, she was like my sister, and she called us a team. And we were a team; we did everything together. It’s been wonderful, and I had a great life because of her. All I ever wanted to do was be around horses, and she made that happen for me.”

As her children grew up and moved on to larger horses and other pursuits (her late daughter Beale Morris was short-listed for the 2000 Sydney Olympic eventing team), Wright amassed a small collection of ponies. With her philosophy that “every horse needs a job,” Wright soon began using them to learn how to drive. One auspicious day, she and Trefry spectated at a combined driving event in Pennsylvania.

“We watched Clay Camp with his four-in-hand drive over the top of a log in the marathon, and we were like, ‘We want to do that!’ ” remembered Trefry. “That’s how we got started.”

Using a trio of related Connemara-Thoroughbred geldings—Greystone Sir Rockwell, Greystone Sir Oliver and Greystone Billy Moon—Wright pursued her new sport with the same zeal she embraced anything horse-related. In training her driving horses, Wright applied the many dressage lessons she had learned decades earlier from Wätjen, schooling the horses both under saddle as well as in harness.

“Back in the day, people weren’t such big riders of their driving horses,” said Trefry. “That was a bonus for her, because they got a lot of dressage work under saddle. Her eventing certainly contributed to her driving.”

Trefry soon found herself coordinating trips to Europe for horses, carriages and more.

“My strong point was doing the paperwork and the organizing of all that—she was the ‘get out there and know the horse and do the job,’ side of it,” said Trefry with a laugh. “Paperwork was never her strong suit. She was interested in being outside, loving the outside, and loving animals.”

Soon, Wright and Trefry began organizing driving events. Wright designed the hazards personally, and she helped Trefry and others with their construction. She often used her signature yellow and gray jeeps like they were bulldozers. One time, she overheated her Jeep after hay got into the radiator when she was using it to push 450-pound bales onto a dump truck to make a hazard.

“It was so rewarding to her, to design these obstacles so that people would really need to think,” said Trefry. “She put so much thought into it, and people always said they really appreciated her designs. She was a bit of an artist and creator that way.”

In 1991, Wright and her Connemaras competed at the Pairs World Driving Championship in Zwettl, Austria, where the U.S. team earned its first gold medal in history. The victory, in some ways, meant more to Wright than her groundbreaking Olympic appearance, recalls Trefry.

“When she got her medal in the Olympics, she didn’t feel like she earned a medal, even though she did a great thing for women in the sport,” said Trefry. “She never credited herself with earning the Olympic medal [because hers was the drop score].

“When she did the driving—and in each section she earned a place—that medal meant the world to her, because she felt she’d earned it,” she continued. “She didn’t take anything for granted. She worked hard, every day, for everything. Winning that medal was rewarding for her—that was a dancing-on-the-table moment.”

“When she got her medal in the Olympics, she didn’t feel like she earned a medal, even though she did a great thing for women in the sport. … When she did the driving—and in each section she earned a place—that medal meant the world to her, because she felt she’d earned it.”

Diane Trefry

Wright took particular pleasure from the process of conditioning a horse for his job, and she did most of this work herself. She was dismayed that sports she loved—including eventing and combined driving—changed their formats in recent years to reduce the emphasis on endurance.

“It was kind of sad for her, as time progressed and those things were taken away, because conditioning was so rewarding for her,” said Trefry. “So the 100-mile endurance was really the next step.”

Wright, who had previous experience in shorter endurance and competitive trail rides, made her 100-mile endurance debut in Vermont riding a purebred Connemara stallion—and she quickly learned that he wasn’t the right mount for the job. And that was how Wright, a devoted Thoroughbred lover who had once quipped that “she would never have an Arabian come down this driveway,” had to “eat her words,” according to Trefry.

“We joked with her a lot about that,” said Trefry. “After the ride in Vermont, she said, ‘I guess we need an Arabian.’ So we went out and got an Arabian. It didn’t take her long to figure out there are horses that are really bred for it.”

Wright and LL Stardom were selected for the 1999 Pan Am Games in Winnipeg, Manitoba—even though she never specifically verbalized that as her goal—and yet again Wright found herself representing her country on a championship team, in a third sport.

“That’s just the way she was,” remembered Trefry. “Everything she did, she reached for the stars—and she usually reached them.”

A Tradition Of Excellence, Shared

Though Wright may never have set out to be a role model for other women in equestrian sport, her commitment to excellence and success in anything she set her mind to helped shape countless horsewomen—including those who never had the opportunity to meet Wright in person.

“She made things happen, and if she said it was going to happen, she was going to make it happen one way or the other,” said Trefry. “She was an amazing motivator. A person might say no to you or me, but she always managed to get that easy yes. She would never ask you to do something she wouldn’t do. She got down in the trenches, she dug the post holes, she marked the courses.”

Five-star eventer Sharon White was a teenager when she first met Wright through her daughter Beale. The family embraced White, offering her experiences that changed her life and the arc of her professional career.

“I was so unbelievably lucky to have met them—it’s like you don’t know what you don’t know, and I just happened to end up at an eventing barn when I started riding lessons,” says White, 51, of Summit Point, West Virginia. “I basically knew nothing, and then to be put into Lana’s hemisphere, into her world, was huge. I pride myself on my horsemanship, and so much of what I know I learned from her. Lana has got to be one of the best horsewomen I have met in my entire life.”

White spent time at both Unicorn Farm and Wright’s summer residence in Reading, Vermont. In each place, Wright guided the young people in her orbit, often without saying much at all.

“Lana had a very distinctive voice, and I remember it would get so bemused when I would do something [wrong],” recalled White. “She would say, ‘I don’t know what you’re doing, Sharon.’ She never meant it to be this way, but you knew you were doing something stupid. She was so cut and dry.

“But she was never one to make you feel like you were in the presence of all she had done,” she continued. “She was always so approachable in anything that had to do with horses or horsemanship, and so thoughtful, so dedicated to it. You just felt like she cared so much about the horses, that you could ask her anything about them. It would really matter to her.”

Suzy Stafford made history of her own in 2005 when she became the first U.S. combined driver to win an individual world championship, but as a junior, she was an eventer and a member of the Middletown Pony Club. A serious riding accident in her late teens meant that a professional riding career was no longer in the cards, and it was Wright who helped Stafford start in driving.

“She was certainly an inspiration, and a force to be reckoned with in anything she did,” said Stafford, 48, who is based near Fair Hill, Maryland.

“It was always two hundred percent or nothing. In that sense, being around her at the farm, it was certainly influential in my experience in driving. Watching someone with that level of drive and talent and experience was very inspiring to me.

“She never thought anything she did was special, or significant, or anything like that,” she added, “it was just how she carried on her day: We train horses. We go and win medals. That’s just what we do.”

Stafford remembers that Wright held everyone to the same high standard, and she wasn’t afraid to call someone out if a detail was amiss. But in doing so, she showed each person they were capable of more than they thought.

“It’s rare to find someone with the high standard she held for herself and the people around her,” said Stafford. “In a sense, those were the most important lessons she taught.”

While Wright may continue to be best known for her historic Olympic appearance, perhaps she would prefer to be remembered for her many and varied contributions to equestrian sport, from the grassroots level up.

“She wanted everyone to get the rewards she got,” said Trefry. “She got medals. But she gave way more to the equestrian world than she ever took from it. And she took pleasure from doing that, as well.

“It was about teaching everybody to enjoy the horse, at the lowest level, the medium level, or the highest level—whatever is for you,” she continued. “It made no difference. Anything to enjoy the horse, and learn to care for the horse, and the importance of the horse. For Lana, it was really about appreciating, enjoying, and making the most of your horse or pony, no matter what he was.”

This article originally appeared in the July 2025 issue of The Chronicle of the Horse. You can subscribe and get online access to a digital version and then enjoy a year of The Chronicle of the Horse. If you’re just following COTH online, you’re missing so much great unique content. Each print issue of the Chronicle is full of in-depth competition news, fascinating features, probing looks at issues within the sports of hunter/jumper, eventing and dressage, and stunning photography.

The post Throwback Thursday: Lana duPont ‘Did It Because She Loved It’ appeared first on The Chronicle of the Horse.

]]>The post Throwback Thursday: Look How Far Courses Have Come appeared first on The Chronicle of the Horse.

]]>The Aug. 31, 1962, issue included a report on the Inverness Two-Day Event in California. The event was described as a “prepatory meet designed to prepare horses and riders pointing toward the Wofford Cup trials at Pebble Beach.” The report included this amazing photo of the water jump, taken by Tony Vacek and captioned simply “Ernest Simard II on Paddy Boals at one of the obstacles in the cross-country”…

Ernest Simard II on Paddy Boals negotiate the water jump on cross-country at the Inverness Two-Day Event in California in 1962. Tony Vacek Photo

The article said the course didn’t “lend itself to a true galloping course, but packed into the 2 miles of cross-country, following 3 miles of up-and-down roads and trails, were two mighty interesting obstacles built to test the boldness and cleverness of horse and rider.”

The water jump was on of those, and it was Fence 3 on course. “The cross-country led along the left side of the valley to the beach where obstacle No. 3 consisted of going out into the bay alongside a pier and passing underneath it between the last sections of pilings, and thence back to the shore.

“Whether the horse waded belly deep or swam depended on his size as well as his mood!”

The course description also included “an overturned dinghy 3 to 4 feet in height and 7 feet wide,” and “a heavy post and rail fence at the top of a slide into a stream with another post and rail fence out of the water.”

Then, in the Aug. 27, 1966, issue of the Chronicle, there’s this photo published with simply a caption and no accompanying story…

Ron Burton on Sea Breeze negotiating the slide in the Handy Hunter Working class. They won the third place ribbon. Chronicle File Photo

The caption reads, “Ron Burton on Sea Breeze negotiating the slide in the Handy Hunter Working class. They won the third place ribbon.” The show was the Valley Hunter Show in Valley Park, Missouri.

Can you imagine this hillside in a handy hunter class of today?

This last photo didn’t appear on a course in competition (thankfully!) but it’s worth highlighting for its sheer insanity.

A Spanish Army Riding School student jumps a ditch that was part of the final three-day event exam for second-year students.

The article it ran with was in the Sept. 14, 1962, issue of the Chronicle about the Spanish Army Riding School. This ditch was part of the final three-day event exam of the second-year students.

Here’s the article about the school, which must have turned out fearless and skilled horsemen…

“The ‘School’ has always strived to be a superior institution where officers from all branches of the army could perfect their riding, and eventually give the ‘Spanish Style’ a place in international competition. This could only be accomplished through excellent instruction, concentrated effort, and plenty of willingness on all sides (the horses included).

“At first a one year course was considered sufficient; but experience proved this theory wrong. In a year’s time the student remained rigid, unrelaxed in their adjustments to the School’s perfectionist instruction. They evidently needed a second year in which to ‘loosen up’ and gain confidence in themselves; they had to be able to apply their training to several different types of horses. For this reason, the School created a second year course for the selected students of the first year. This also gave an opportunity to spread out a rather crowded training program, leaving the more difficult phases for the second year. Some of these phases were the preparation of race horses, polo, and three-day events, which all call for a more experienced and self-confident rider.

“When I say all the more difficult phases were left for the second year student, I omitted probably the most impressive feat of the Spanish Army Riding School: ‘las cortaduras.’ This is reserved for the first year students, and for a very good reason: it separated the men from the boys. ‘Las cortaduras,’ meaning literally ‘the cuts,’ or ‘drop-offs,’ are almost vertical slopes of about twelve meters in height, which the horses, with their somewhat apprehensive first year students, have to negotiate each May. I cannot say that I whole-heartedly agree with what usually terminates in a mass of broken bones on the riders’ part, but I must admit that if accomplished unhurt, it makes one feel as if nothing is insurmountable on horseback. One can be sure, however, that after May, a class of twenty has been temporarily reduced to one-third of its size. The event is witnessed by visiting members of foreign teams, as it coincides with the international jumping competition in Madrid, and by several others; all agree that Spanish riders are of the most daring sort.

“There is no phase of equitation that has not been attempted by the School. The students are even prepared in elementary veterinary medicine and stud management. For a while there was a stud farm right on the premises, which was later transferred to Lori Toki, the Thoroughbred breeding farm run by the School in the north of Spain. From this farm come some of the finest race horses in the country.

“Each first year student must train his own colt—from saddle-breaking on up through a small jumping competition. These colts, at the end of the year, are divided between the respective groups of the School according to their ability. Some go to cross-country jumping, others to dressage, polo, stadium jumping, three-day events (if good enough), and, alas, there is always the poor fellow which ends up pulling the garbage cart!

“Apart from these horses are the yearly inflow of Thoroughbreds from the race track, plus several Irish, French, German and English imports; which all go towards making a complete selection of horses in every field.

“The best students from the second year, after having passed their exams (consisting of a three-day event and several jumping rounds with different horses), are then made sub-instructors for one more year. This completes their formal training and the “cream of the crop” pass on to be number one instructors and possibly international team members.

“The well known ‘Spanish seat’ or style is derived from the French and Italian schools combined. At first the French was considered the better, and then was modified in accordance with the Italian or Caprilli method. Two Spanish lieutenants had gone to Italy for courses and had found the forward seat to be superior to the straighter posture of the French. With these two schools, Spain has developed what they call ‘natural equitation’ leaving the horse completely in the hand but at the same time at liberty to perform his best, with the least interference from the rider. To achieve this, a colt is first trained in dressage and then jumped, follwing the Italian style, with slightly longer stirrups and a few degrees less forward inclination. The rider takes the horse into a jumpby collecting him first and, during the final strides remaining still and letting the horse do the rest.

“With the evolution of modern weapons, the School has its problems. The horse is no longer essential to the Cavalry. Although classes are still carried out as before, this must be done amidst artillery fire in the country and tanks around the stables. Each year there are fewer students and the standards are being lowered because of the lack of competition. Although there are many protests from those truly interested in the preservation of their beloved School, its future is uncertain.”

The post Throwback Thursday: Look How Far Courses Have Come appeared first on The Chronicle of the Horse.

]]>The post Throwback Thursday: Legends Of The Summer appeared first on The Chronicle of the Horse.

]]>This time of year, my thoughts often drift back to the days when I was a kid at summer camp. It was one of the best experiences of my life—a camp devoted to horseback riding where young girls immersed themselves in everything equine for eight solid weeks.

The names and faces of my fellow campers have faded over time. But the horses—those I remember. The memories of the four-legged legends that shaped my summers are as enduring as those hot, humid July and August afternoons.

There was Sunbeam, who was older than Moses and the first horse many a little girl sat on. He had a hitch in his git-along that gave him rambling gaits. His canter was discombobulated and trying to sit it made your lower half feel it was attached to two horses going different directions.

When he trotted, all of his toes pointed to different headings. He would have made a good getaway horse in the old West, because trackers would have had no idea which was he was headed. His riders didn’t really know either, and for that reason it was best to let him steer himself.

Then there was Ivory, the old albino mare. The only way to fall off of Ivory was to hurl your own body to the ground. If she sensed her rider was unsteady she’d just slow down and stop.

Many a kid in the beginner ring plowed into the back of Ivory. It never rattled her, though; she’d just turn her head and look back at the offending horse as if saying, “Seriously? Could you not see me stopped here rescuing this poor, teetering child? Pay attention.” You knew you’d mastered the trot when she went all the way around the ring with you. It was her personal seal of approval.

Captain Mac was a beautiful buckskin whose mission was to see how many campers he could yank out of the saddle by randomly plunking his head down to grab a bite of grass. He could perform this maneuver at all gaits, and he liked to mix it up. Riding him in the dirt arena did not dissuade him, as he had a staunch leap and the net will appear philosophy about things.

You knew he was going to do it, and yet he’d sucker you into trusting him every time. It was like watching Lucy pull the football away from Charlie Brown day after day.

Devil’s Fiddle was a rangy, angular flea-bitten grey with an expression of perpetual disdain. He had a slightly Roman nose and one nostril that would flare distinctly when he was displeased. Which was pretty much all the time. There was smug entitlement about him. Clearly, he considered himself above carrying the hoi polloi.

Fiddle was renowned for having The. Worst. Trot. Ever.

His canter had all the grace of a washing machine with an unbalanced load. Woe betide the unlucky rider who drew Fiddle for the lesson right after breakfast or lunch. They’d flop around like invertebrates, trying desperately to keep their heels and meals down, while Fiddle bobbed around with his signature smirk. It was the only time he looked like he was having fun.

Fritz was a round, squatty bay of indeterminate lineage. Imagine what a Mr. Potato Head horse would look like, and you’ll pretty much be picturing Fritz. The misfortune of being shaped like a wingless bumblebee made Fritz decidedly non-aerodynamic.

Ever foiled by the Laws of Physics and a can’t-do attitude, he was the slowest horse I’d ever seen. Camp lore purported he had actually been seen cantering in retrograde. But he certainly didn’t jump; he never once attained sufficient ground speed for lift-off.

I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention Betsy.

Betsy wasn’t a horse. She was a boa constrictor that belonged to one of the camp’s riding instructors. She lived in the tack room. Betsy was narcoleptic and would randomly take a nap and fall off of or out of something. The tack room was frequently like a scene out of Snakes On A Plane.

She was accustomed to being picked up and would just hold her body in the same shape while you found her a new resting place. Once people realized that the only way she could hurt you was if you tripped over her, she became just another thing to hang up.

Joker resembled a Salvador Dali drawing. He challenged all the rules of conformation. I picture Mother Nature’s architects staring at a blueprint of him and wondering how the heck they were going to make this thing able to stand up on its own. I imagine gyroscopes and whirlygigs in his head fighting to maintain equilibrium, and a man behind a curtain frantically pulling strings and levers to keep him upright.

The Law of Natural Selection had clearly given him a pardon. But you could put the most timid, fearful child on his back and he would make it his sworn duty to carry them safely.

If any of these horses stepped into today’s show ring, they’d doubtless be snickered at. But to us, all of them were beautiful. They were some of our first and finest teachers, and, as great teachers do, they instilled in us a passion that changed our lives.

This was a time before cell phones and the internet, when we regaled our adventures via letters, or in the stories we told when we went back home.

It is entirely possible that things sometimes happened more the way we wanted to remember them than the way they’d actually unfolded.

And it’s possible that, over the years, the facts have been mingled with the fanciful. There are no Facebook posts or YouTube videos to prove something was one way or the other. And that’s a good thing. A little memory, and a little myth—that’s what great legends are made of.

After years of trying to fit in with corporate America, Jody Lynne Werner decided to pursue her true passion as a career rather than a hobby. So now, she’s an artist, graphic designer, illustrator, cartoonist, web designer, writer and humorist. You can find her work on her Misfit Designs Cafepress site. Jody is one of the winners of the Chronicle’s first writing competition. Her work also appears in print editions of The Chronicle of the Horse.

Read all of Jody’s humor columns for www.coth.com here.

The post Throwback Thursday: Legends Of The Summer appeared first on The Chronicle of the Horse.

]]>The post Throwback Thursday: A Father’s Day Tribute To Horse Show Dads Everywhere appeared first on The Chronicle of the Horse.

]]>One of my deepest regrets in life dates back 34 years to a horse-related event involving my father. It was 1975, and I was wrapping up my sophomore year at a Midwestern women’s college, with plans to transfer to a larger university in the fall.

My parents had come to watch me ride in the big year-end horse show—a glitzy, nighttime affair held in the school’s indoor arena, with everyone (spectators and exhibitors alike) dressed to the nines.

That night, I was lucky enough to win the formal hunter hack class aboard a handsome gray gelding named Trackman. To present the trophy, the college president and several regents were on hand, lined up on a strip of red carpet, looking properly dignified in tuxedos and gowns.

Mollie Bailey Photo

Before posing for pictures, I was handed a giant blue ribbon, a bouquet of roses and an enormous silver platter. I recall wondering just how the heck I would manage to juggle all those items while leading the expected victory gallop on a rambunctious Thoroughbred.

Photos finished, I turned Trackman toward the rail. There, right in front of me, was my delighted father—leaning over the arena wall and applauding more loudly than anyone (even whistling, I think).

Now, the noble thing to do would have been to ride right up to him, unload my prizes in his arms and give him a quick hug. The obvious message, for all to see: “Thanks, Dad, for supporting my horse habit for the past 15 years. And for everything else, too.”

Rarely does anyone get the chance to honor a parent so publicly. My dad’s heart would have soared with pride.

So, why didn’t I do the right thing? Why, instead, did I just smile vaguely in my father’s direction and canter off–fumbling to keep my grip on the platter, the flowers, the ribbon and a set of double reins?

That’s a question I still cannot answer, and the split-second choice I made on that night saddens me to this day—especially since it turned out that my father would only grace this earth for seven more years.

Today, as a parent myself, I’m utterly amazed when I analyze an even earlier memory of my dad. I was 13, and had fallen off a runaway pony while stupidly jumping with no tack or helmet (supervised only by an equally irresponsible friend).

The naughty pony had made a beeline for a nearby road, where he thoughtlessly dumped silly me onto the asphalt. Naturally, I banged my head pretty hard upon landing. My father, coming to pick me up that day, turned down the road just in time to see me lying on a stretcher. Paramedics were loading me into an ambulance while my guilt-stricken friend stood by.

Why does this memory amaze me?

Because even after such a jolting scare, followed by a weeklong hospital stay for my fractured skull, my dad (and more reluctant mom) not only let me ride again upon doctor’s clearance three months later, he also bought me my first horse right then. Frankly, I’m not sure I could have been so forgiving and brave for my own daughter, who inherited my equestrian gene and has ridden all her life.

Other memories of my dad’s part in my riding history are of a lighter variety–like the incredibly bad pictures he used to take at horse shows! There were countless snapshots of empty jumps because my horse hadn’t even entered the frame yet, or flat-class images of only a rump and tail going by in a blur–no rider.

But I don’t have a single memory of my father griping about the cost of horse shoes, horse shows or horse stuff in general–all the accoutrements and activities attached to our sport that can end up costing a small fortune.

Private lessons, vet bills, new saddles, shipping fees, sale commissions—Dad would just gamely write the checks. I did sometimes hear him jokingly lament to his friends about how his daughter was more interested in horses than in boys, which I admit was quite true until later in my life. Yet I never heard him complain for real.

The Torch Is Passed

Two decades later, my husband took on the role of horse show dad to our oldest daughter—a part for which he never willingly auditioned, but grudgingly came to accept as inevitable. And bless him, because like my dad, he also was a (relatively) good-natured writer of large equine-related checks, and a tireless ringside cheerleader.

In the early years, when terms such as “swapped leads,” “chipped in” or “handy hunter” sounded like a foreign language to him, my husband determinedly strove to find an amiable niche for himself at our daughter’s lessons and shows. He usually ended up hanging out with other dads in the stands or in the tack room, where they could slip into the much more familiar conversational territory of football scores or stock market trends.

No doubt there are horse show dads who, while enormously proud of their offspring’s riding achievements, might secretly wish that their children played mainstream team sports, the rules of which generally make a lot more sense to the average male.

Some riders do play such sports, of course, but it seems to be the exception rather than the norm. Now that our college-age daughter rides on a varsity equestrian team in a realm that’s largely governed by NCAA rules, I’ve seen a marked rise in enthusiasm from my husband, because this is the closest he’s ever come to finding his comfort zone in the strange and complicated world of horse sports.

At regular circuit shows, other dads may find their own comfort zones by volunteering to pick up meals, shoot video, tip the grooms, etc. There’s definitely a special place in heaven for these placidly patient fathers, who, unlike the majority of their counterparts, those very hands-on horse show moms, often hover on the far outer fringe of the action, no matter how much they might inwardly desire to be more involved.

Of course, attempts at such involvement can be tricky, as we’ve all serenely observed at one time or another. There’s the dad who’s called upon to temporarily hold his child’s show horse, standing there gingerly clasping the very tip of the reins while the liberated animal gobbles forbidden grass.

The dad who mistakenly starts whooping before a jumping round is over, totally mortifying his kid. The dad who loudly snaps open a folding chair as a hunter approaches a nearby oxer, inadvertently triggering a violent spook. Or the dad who innocently follows the trainer right up to the in-gate as his child enters the show ring, obliviously chattering on about random subjects as the child is navigating her course.

I vividly remember one of my first horse shows with my friend Ruthie, the summer when we were both 8. Mounted on our ponies, wearing dark woolen hunt coats under an unusually hot Michigan sun, Ruthie and I had to wait an interminable amount of time for an equitation class that kept getting delayed.

In sympathy, Ruthie’s dad kept bringing her Cokes to drink, which she gratefully accepted, chugging down every one of them. Well, you can guess what finally happened: Ruthie spectacularly vomited just a few feet away from the judge, who had chosen that precise moment to finally show up at the ring. Ruthie’s dad was understandably chagrined.

But we do so adore him, this particular type of horse show father (and indeed all types, including the fully knowledgeable ones) because everything he does is motivated by the very best of intentions. How can we possibly fault that?

So girls and boys, ladies and gentlemen: The next time you spot your dad waving to you from the rail after you’ve won a class, seize the moment and hand him the trophy, or at least blow him a kiss. You don’t even have to wait until Father’s Day to do it. And trust me, you’ll both remember the moment forever.

The post Throwback Thursday: A Father’s Day Tribute To Horse Show Dads Everywhere appeared first on The Chronicle of the Horse.

]]>The post Throwback Thursday: A Classic Photo Of Two Legends appeared first on The Chronicle of the Horse.

]]>

Howard Allen Photo

This is a photo of the inimitable grand dame of horse shows, Sallie Wheeler (though at the time this photo was taken, she was Sallie Motch—married to her first husband, Robert Motch) riding the famous mare Isgilde at the 1964 Upperville Horse Show.

Look at her perfectly coiffed hair under that classic top hat (back then helmets just weren’t worn and style triumphed over safety). It must be an appointments class, because she’s got her hunt whip in her right hand, and if you look closely, you can see a pair of gloves tucked under the saddle flap. The flared breeches were standard in the days before stretch fabrics, and her shadbelly is of an understated cut, with curved tails.

Look at her position, perfectly balanced over the center of the horse, with a nice softness in the reins and her eyes looking to the next jump. She’s using a hunting breastplate and a running martingale—now breastplates are very rarely seen in the hunter ring and the only martingale that appears is a standing (though running martingales are still legal!).

I know Isgilde jumped in perfect hunter form, because I’ve seen other photos of her. But this photo is timed as so many of that era were—in the beginning of the landing phase of the jump. Back then, the emphasis wasn’t so much on the “perfect” moment of the tightest knee-tuck, but on the forward-going and boldness of the horse, and this moment captures that quest for the next fence perfectly.

It’s interesting that you can clearly see Isgilde’s warmblood brand on her left hindquarter in this photo—she was one of the very first imported warmbloods in what was then a hunter ring dominated by Thoroughbreds.

The process of finding photos that ran in old Chronicle issues isn’t an exact science. Before around 1972, there is no index of the issues, so there are 37 years of weekly issues filled with history and you never quite know what might be in one when you open it. Flipping through a bound volume of issues from the 1960s, you can find a photo, ad or article that embodies the history of our sports on almost every page.

If you see a photo you’d like to use or look at more closely, then you have to traipse up to the attic of the Chronicle building and consult the photo archives. Starting in the 1950s, the photos are organized into folders by issue date, so I found this photo in the June 19, 1964 folder in the file cabinets. Photos from the ‘30s or ‘40s, however, were not so thoughtfully organized, and they’re in folders arranged alphabetically by subject, so it’s almost impossible to find a specific photos. But shuffling through those stacks of prints is an exercise in time travel—absolutely fascinating.

This particular photo was used in a “Guess Who” collage printed on the back cover of the magazine. Back then, “cut and paste” was quite literal, so the print photos that made up this collage had been cut into different shapes, then glued to a piece of paper in an artful design and numbers glued to their fronts. Once the magazine was printed, they were pulled off that paper and filed away without much care as to their preservation.

Flipping through bound volumes of the Chronicle and perusing the photo archives is a trip down the lanes of the very history of our sport. I always learn something and am always enchanted.

“Throwback Thursday” might be a child of social media, but it’s also become one of my favorite assignments. I think it’s a great way for us to bring to light gems of history like this that lie hidden in the pages and files of the Chronicle.

The post Throwback Thursday: A Classic Photo Of Two Legends appeared first on The Chronicle of the Horse.

]]>The post Throwback Thursday: US Eventing Team Proved Their Mettle In Los Angeles appeared first on The Chronicle of the Horse.

]]>When the five members of the U.S. Olympic three-day team pulled out of their training camp at South Hamilton, Massachusetts, on July 8, leaving behind coach Jack Le Goff, they put themselves out on a limb. If they came home with the team gold and individual honors, they would look brilliant. It would mean they were experienced international competitors who knew how to prepare their horses. But if they failed, their actions had left them wide open to criticism.

The limb held. The American team of Mike Plumb, Karen Stives, Torrance Fleischmann and Bruce Davidson rode brilliantly to narrowly defeat the World Champion British by 3.2 points, as Stives came within one show jumping rail of being the first woman ever to win the individual gold in the Olympic three-day event. Still, she and Virginia Holgate of Britain, who took the bronze behind Stives and gold medalist Mark Todd of New Zealand, were the first individual female medalists in this discipline.

The Americans achieved their victory by becoming a team, something many feared they wouldn’t be able to do after 10 grueling and competitive weeks of trials before the final turmoil. They became a team because they wanted to, because they had to to win.

“I think basically we’re all pretty good friends and we had to do what we had to do,” said team captain Mike Plumb. “We came back from a gallop at Hamilton and decided we couldn’t stay—there was no place to do the conditioning. (Insects were also cited as a problem). We never really sat down and decided to become a team, it just sort of happened after Ledyard. So we met with Billy Steinkraus and decided to leave.”

“We definitely made an agreement that we would all work together.” said Le Goff during the second day of dressage. “We have reached a consensus that we will go for the team medal as a priority. So that means people will ride to orders (on cross-country) according to speed and what is needed.”

Karen Stives concurred. “We’re all out for the team and everything is great with Jack, and that’s no lie,” she said after her dressage test.

So for one week these talented, outspoken and individualistic riders put aside any real or imagined differences, pulled together and did the job they were selected to do.

So for one week these talented, outspoken and individualistic riders put aside any real or imagined differences, pulled together and did the job they were selected to do.

“This one has meant more to me than any other Olympic Games,“ said Plumb, whose gold medal made him the only two-time gold medalist in U.S. equestrian history and raised his total to six, also a record. “Winning the gold here meant more to me than Montreal. We’re a pretty close group, and more than any other time it was a real team effort.”

Cheers From The Crowd

Two days in the heat and smog at Santa Anita racetrack before more than 22,000 mostly partisan fans were really a preview of things to come. The U.S. took a 17.2-point lead over Sweden, the ’83 European Champions. The French, winners at Fontainebleau in 1980, were third, and the co-favored British trailed by 21.8 points. Bruce Davidson, riding fourth on the team, was second with a very forward and accurate test on J.J. Babu and Karen Stives and Ben Arthur were third.

Ben Arthur’s forward and free test, in which he appeared more “connected” than in his most recent efforts, was especially remarkable because he had been feeling full of himself all week and especially when Stives first got on him at 6 a.m. Sunday morning. That early workout was what he needed.

“He was so wonderful from the moment I got on him (to warm up for the test),” Stives said. “At Ledyard (the final trial) I really liked my warmup, but he wasn’t so good in the test, and I was crushed. When we went back to work, he was much better—we’d go through about three good days and then have a bad one. I guess that happens whenever you reach a new level of communication.”

Torrance Fleischmann placed 10th although Finvarra was behind the bit and slightly on the forehand at the trot but lovely at the canter. Plumb was 16th on Blue Stone.

The leader was the lone Swiss rider, the ’81 European Champions, Hansueli Schmutz and the 11-year-old Dutch-bred Oran. The chestnut gelding and his tall, thin rider put in a free and relaxed test in which Oran appeared at times to be above the bit. But this seemed to be what Francois Lucas (France), judge at M, and Anton Buhler (Switzerland), judge at C, wanted because both placed him first with 179 good marks. Lucas had Ben Arthur second at 170, but Davidson sixth and Fleischmann 19th.

Being the leader after dressage was not new for Schmutz. He was in the same position last August at the European Championships on his home turf at Frauenfeld. However, there he began the cross-country course too fast in the unusually hot weather and Oran fell late in the course.

“I rode a terrible cross-country,” Schmutz said after dressage. “I am determined not to make another mistake such as that. I hope I have learned a lesson.”

Lurking in fourth place, less than three points behind Davidson and Stives, was New Zealander Mark Todd on the small but courageous Charisma. The pair had beaten the entire British team except Lucinda Green in finishing second at Badminton this April, thus stamping themselves as genuine medal contenders, and now they were well placed before Charisma’s favorite phase.

Brilliance And Luck

As always at an international three-day event, attention focused on the cross-country course, a two-hour drive south of Santa Anita at Fairbanks Ranch. Unlike most international courses, however, the course at the Fairbanks Ranch Country Club had never been ridden before, so riders and coaches weren’t really sure what to expect. Fortunately, assurances that the weather at Fairbanks would be cooler and the air clearer proved true, preventing a repeat of the exhausting conditions at the 1978 World Championships. The almost 4 1/2-mile course criss-crossed the golf course constantly, meaning the path traversed moguls and hillocks designed to add variety to a golf course, not to provide good footing for horses. The riders agreed the fences were beautifully designed and built, but that the track was terrible.

“Olympic courses have not been known to be what they should be—the most difficult courses in the world. I think this one is harder than Montreal and Mexico and on a par with Fontainebleau,” said Plumb. “But the track is not what you’d hope it would be. Because of the hills and the incorrect banking on most of the turns, they never get all four feet on the ground.”

Plumb’s concerns were echoed by World Champion and gold medal hopeful Lucinda Green, who called the course “featureless.” British chef d’equipe Maj. Malcolm Wallace said, “Each fence taken individually is fair, but together it’s a tough test.”

Le Goff predicted that not one would make the optimum time because of the heat and poor footing and that the conditions would favor smaller horses with shorter strides, like J.J. and Finvarra, while hindering bigger horses like Ben Arthur and Blue Stone.

“I think it will require a lot of good sense,” said the coach of 14 years, who will leave on a high note since he is retiring at the end of the year. “My feeling is that once you get to the 10-minute box, you may as well leave your watch behind. You just have to ride what you feel.”

The coach was both right and wrong. Plumb and Blue Stone blazed the trail for the U.S., coming home 13 seconds slow with no jumping faults, despite some rather awkward efforts as Blue Stone appeared to tire. Plumb told his teammates the course was even more slippery than they had thought—he said his horse slipped and almost fell five times—and told them to put in bigger studs. Three horses earlier, the first British rider, Ginny Holgate on Priceless, had shown it might be possible to make the time. The big-boned English-bred finished only 1 second slow with a truly priceless performance. But not until Ben Arthur, the 17th horse on course, was there a clear round. Only three more horses—Regal Realm, Charisma and Master Hunt (Marina Sciocchetti of Italy)—would go clean, with Charisma the fastest. In a way, Ben Arthur’s near-perfect performance shouldn’t have been too surprising since he had gone the best under the most difficult circumstances this spring. The gray Irish-bred was the only horse to make the time over Ship’s Quarters’ twisting and undulating course and had the fastest time over the rain-sodden course at Green Spring Valley. With his long, effortless stride and great scope, Ben Arthur met every fence at Fairbanks perfectly, faltering only on landing in the first pool at The Waterfalls.

“It rode much better than I thought it would,” said Stives. “He handled the turns really well—just like a slalom skier. But he never gives me a feeling he can’t handle it. He’s always solid.”

Stives’ mother, Lillian Maloney, was proud of both her daughter and the horse that Maloney picked at the World Championships in Luhmühlen barely two years ago. Although not a horsewoman, Maloney has an uncanny eye for equine talent—she also picked Stives’ former star The Saint—and at Luhmühlen she told Stives to get first refusal on Ben Arthur despite Stives’ protests that he was too big and difficult in show jumping. On Wednesday, Aug. 1, despite the anxiety she now feels since Stives’ horrible fall at Kentucky in 1982, Maloney had reason to believe her stars were going to do well.

“I was out on the course before Karen went and I met this movie star—what was his name?” she asked her husband, Bob, at the final vet check on Thursday morning. “William Devane, that’s right. He told me. ‘I’ve already picked the gold medal.’ and I said, ‘Oh really? Who?’ He said, ‘Karen Stives, she has the best horse.’ Then he wouldn’t believe I was her mother!”

Stives was saying that second wouldn’t be so bad, but her mother was thinking gold even though Ben Arthur was less than a rail in front. “I blame my friend Jack Burton for this,” she said with a smile, pointing to the dressage scores. Gen. Burton had placed Charisma first with 173 good marks (to 147 and 142 from the other judges) while giving Ben Arthur 157. Meanwhile, the British were hanging tough, as 30-year-old Ian Stark, representing Britain for the first time, got around with 7.2 time faults. However, their third rider, Diana “Tiny” Clapham on Windjammer, fell at fence 7.

The U.S. only had a little breathing room, though, when Torrance Fleischmann rode into the vet box on Finvarra. Only a week before, Finvarra had hit his head on a screw eye in his stall and given himself a hairline fracture of his skull near the right ear. Now the gallant chestnut, competing in only his fourth three-day event, was tied up. Under normal circumstances. Fleischmann wouldn’t have gone, but this was the Olympics. Her husband, Charlie, got Finvarra past the vet inspection by “falling on my face” to distract the judges while he jogged the horse. Finvarra spooked and judges asked to see him again, but he had loosened up enough to pass. Finvarra had no jumping faults, although Fleischmann had to hit him for the first time in his life and finished 7 seconds slow. The next morning Fleischmann had high praise for the work team veterinarian Marty Simenson and Finvarra’s groom, Debbie Furnas, had done, but she didn’t know whether to tell the whole world how brave her horse was or to be ashamed of herself for making him go.

“He really showed me something yesterday,” she said with emotion. “He’s the bravest horse I’ve ever ridden. I was really just riding the horse, not the course, out there. Now I know what it means to ride in the Olympics—riding a horse that’s not 100 percent and giving it everything you have.”

Britain’s final combination, Green and Regal Realm, came through with their usual flawless cross-country performance to keep the Brits close. Then, Bruce Davidson entered the starting box with a chance to take the individual lead and keep the U.S. comfortably in front. Leader Hansueli Schmutz had had a refusal at fence 7, the Bridge and Walkway, where horses jumped down a small bank into a pond, up onto a 9-foot-9-inch-wide bridge, over a 3-foot 5-inch rail back into the water, and up a bank to exit.

Number 7 was the course’s bogey fence. Stives said it was like doing a gymnastic combination—either it worked out or it didn’t. It worked out beautifully for Ben Arthur and Charisma, but not for Oran or J.J. Babu. The American horse jumped in big, slipped, made a big leap onto the bridge, and found his chest against the rail. Davidson calmly turned him around, tried again and continued.

“He jumped into the first pool like he thought it was really deep,” Davidson said. “It was like going down into your basement with no lights and looking for the floor—and not finding it.”

Davidson bristled at the suggestion that there was something wrong with J.J. Babu because this was his third refusal in the last year, the others being at the Trout Hatchery at Burghley (England) last September and at the Coffin at Kentucky this May.

“I don’t think there’s anything wrong with him,” Davidson insisted. “There’s an explanation for each refusal. They’ve all been on great, big courses that caused lots more trouble than that. J.J. still has all my confidence.”

Nevertheless, because of bad luck the one title Davidson has not won had again eluded him and the U.S. was less than two rails ahead of Great Britain with one phase to go.

One Gold Gained, One Lost

For the first time in Olympic history, show jumping was conducted in reverse order of placing, meaning the pressure and excitement had a long build-up since three of the four British and all four Americans were in the final 15 of the 40 riders. The three of the four young riders on the German team (all were under 30 and two were 21) went clean to hold on to third place, a finish they and their coach, Bernd Springorum, were thrilled with. Davidson pulled a rail, as did Plumb, narrowing the U.S. lead to less than a rail. Stark pulled a rail, but Green delivered a clean round, and Fleischmann responded likewise despite Finvarra’s previous problems and a case of food poisoning she contracted on Thursday. Holgate then went clean to clinch at least an individual bronze and a team silver, and Todd and Charisma went clean despite touching almost every fence, as he had at Badminton.

“That’s a little trait of his. He likes to feel his way around the course. It’s a little nerve wracking,” Todd joked later.

Two gold medals were up for grabs as Stives and the athletic Ben Arthur cantered into Santa Anita’s stadium to a deafening roar. Pockets of applause broke out and were quickly quieted as they cleared the first 10 fences. But Ben Arthur jumped flat in the triple combination and pulled the middle element. The individual gold belonged to Mark Todd, but by keeping the last fence up, Stives kept the U.S. in front for the prize all four riders said they really wanted.

Watch Stives silver-medal-winning round:

Stives was asked later what she thought when the rail fell. “Not to have another one,” she quickly replied. “The only real pressure was for the team, and I knew we had only one rail, so I wasn’t devastated. I think the silver medal is terrific, and I never expected it. I’m a born pessimist, and when I don’t expect things, they mean more.”

For Todd, 27, becoming the first equestrian medalist in the history of New Zealand had been a long road. His first international event was the 1978 World Championships in Lexington, and since then he has trained on and off in England. In 1980 he won Badminton on the New Zealand-bred Southern Comfort, whom Torrance Fleischmann bought and rode in the 1982 World Championships. In 1983 he finished ninth at Badminton on Felix Too, whom he’d only ridden a few weeks. This March he returned to England, “primarily to have a go at Badminton and to have a go at this. But I think we’ve been preparing for this much longer,” he reflected.

Charisma, who turned 11 during the games because New Zealand horses celebrate their birthdays on Aug. 1, had a varied career before being united with Todd 18 months ago. He show jumped and evented before being shown Prix St. Georges by Jenifer Stobart, a Chronicle correspondent and former riding instructor at the Foxcroft School in Middleburg, Va. With Todd, the agile and quick brown gelding won three New Zealand events before finishing second at Badminton. Todd was asked several times whether Charisma would be for sale after the Games, but he said the horse’s owners, his sponsor Woolrest International and Mrs. Fran Clark, had not yet decided. The individual medal ceremony was loud and moving, but not nearly as emotional as the team awards. The crowd of over 28,000 began to cheer as soon as the special Olympic anthem ended, before they could even see the American horses in the tunnel. And when they appeared, everyone was swept up in euphoria. After years of training and months of competition and controversy, they had finally done it. And at home, which made it even better.

I think it’s the best national anthem in the world, and everybody has to stand and listen to it.”

Bruce Davidson

“I don’t like to cry, but it entered my mind,” said Mike Plumb.

“And he does cry a lot,” said Bruce Davidson. “It was like a dream come true. I think it’s the best national anthem in the world and everybody has to stand and listen to it.”

“I think about all the people who made it possible, without whom I—none of us would be here,” said Torrance Fleischmann. “It’s going to pull the heart strings every time. It’s a dream I’ve had since I was a little girl.”

“They’ve said it all,” said Karen Stives, before adding, “The best thing is everything is over, and we won the gold. I feel relieved.”

This article originally appeared in the Aug. 17, 1984, issue of The Chronicle of the Horse. If you’re just following COTH online, you’re missing so much great unique content. Each print issue of the Chronicle is full of in-depth competition news, fascinating features, probing looks at issues within the sports of hunter/jumper, eventing and dressage, and stunning photography.

The post Throwback Thursday: US Eventing Team Proved Their Mettle In Los Angeles appeared first on The Chronicle of the Horse.

]]>The post Throwback Thursday: 1984 Olympic Show Jumping Team Lived A Dream At Santa Anita appeared first on The Chronicle of the Horse.

]]>Hollywood scriptwriters probably wouldn’t write a script describing what really took place on Tuesday, Aug. 7 and Sunday, Aug. 12, only a half hour’s drive from Tinseltown. In fact, producers would probably say it was too good to be true.