The post Wilde Hilde Survives Two Severe Setbacks On Her Way To NAYC appeared first on The Chronicle of the Horse.

]]>In the past three years, the jumper mare has staged unexpected comebacks from both those conditions, and now she’s headed to next week’s Gotham North/FEI North American Youth Jumping Championships, being held Tuesday through Sunday in Williamsburg, Michigan, with rider Haley Honegger, 14, to compete in the pre-junior division. Honegger is among the first group of riders named to receive the new USET Foundation Performance Pathway Grant.

The feisty 14-year-old Holsteiner (Cardino—Linda Vergoignan, Acord II) first overcame a 2022 accident in which she stepped on a roofing nail that punctured her hind hoof and narrowly missed her joint capsule. Just months after returning to competition from that injury, she was diagnosed with the muscular disorder myofibrillar myopathy, or MFM, while getting ready to compete at the Markel/USHJA Zone Jumper Team Championships (California), and yet again, she was on the brink of a career-ending health issue.

“It definitely was very hard for me, because she’s my heart horse, and having her out was very hard,” Honegger said. “I enjoy riding her so much, but I was just hoping that she would be OK. I didn’t really care if we could go back in the show ring. That would be the goal, if we could compete again, but I just wanted her to be happy and fine.”

A Wrong Step

Wilde came to the Honeggers’ barn in Elizabeth, Colorado, in 2020 from a connection Honegger’s parents, Alexia and Patrick Honegger, had in Switzerland. An all-around rider, Haley formed a strong partnership with “Wilde” after learning to adjust to her speed and way of going, and they found success in the junior jumper ring. Though they spend most of their time in the jumpers, they’ve done everything from herding cows to jumping cross-country.

“I definitely think that Wilde feeds off me a lot and that she’s the horse version of me,” Haley said with a laugh. “She can be very calm and snuggly, or she can be like a firecracker in the show ring, where she’s ready to go and will do anything.

“She’s really cool; she’s brave,” Haley added. “I definitely love riding her in the bigger levels, but also I’ve taken her swimming in the ocean and stuff. It’s really fun to have a horse you can go compete the big jumps on and then go chase a cow or something afterwards.”

“The mare really, really tries, and she takes care of the girl,” said her mother, Alexia. “She knows that’s her job is take care of the girl. And she’s got super heart. And anytime some new horses come in that Haley’s riding, she’s very protective over Haley, which is really quite cute.”

In August 2022 Wilde, who lives out 24/7, stepped on an old roofing nail in her field, and it punctured her left hind hoof. She had a corrective rim pad under the shoe on that side, and Alexia believes the pad helped save the mare from what could have been a career—or life-ending—injury.

“The nail got stuck on the pad, which is why it didn’t actually puncture the joint capsule,” Alexia said. “That’s what saved her.”

She was out for several months but recovered completely from the puncture wound. A year to the day of that accident, Wilde and Haley earned an emotional individual silver medal in the children’s division at 2023 NAYC (Michigan). They also helped their combined team from zones 7, 8 and 9 earn bronze.

“It was a very special moment for me—my first year at Young Riders—it was a very proud moment for me, because my mare that I almost lost has now won a medal at NAYC,” Haley said.

A Sudden Onset

The pair spent most of 2024 jumping in 1.30-meter junior jumper classes and small grand prix classes and were at the Markel/USHJA Zone Jumper Team Championships (California) in October 2024 when disaster struck again.

Haley had just finished a warm-up round when she felt something wasn’t right with Wilde after leaving the ring. The mare seemed to be having a hard time moving—and then suddenly she couldn’t walk.

Haley managed to slowly lead her back to the barn, but once Wilde was in the stall, she started urinating blood and wouldn’t move. When veterinarians arrived, they pulled blood and gave her fluids. They determined she was tying up and going into kidney failure. The veterinarians got Wilde comfortable and on fluids for three days until she was able to be transported home.

Once home, Dr. Kelly Tisher, DVM, of Littleton Equine Medical Center, who treated Wilde for her hoof injury, did a biopsy and determined Wilde had MFM.

MFM is a genetic disease, with symptoms that are often similar to polysaccharide storage myopathy (PSSM). MFM affects the muscle cells of a horse, disrupting the alignment of contractile proteins called myofibrils. It presents most frequently in warmbloods and Arabians, and can look like infrequent episodes of tying up. In warmbloods, it often shows up between the ages of 8 and 10. Poor performance, unwillingness to go forward, poorly localized hind end lameness, sore muscles and drops in energy levels are common signs.

Alexia said Wilde previously had mild tying up episodes that resolved within a few minutes over the few years they’d had her, but she thinks that they were able to stave off a severe episode into her teens because of the mare’s lifestyle of living out and eating a diet high in protein and low in sugar, including alfalfa. After her diagnosis, veterinarians recommended a similar diet and routine and prescribed Kentucky Equine Research’s MFM pellet, which is high in amino acids.

“The biopsy was interesting, because it showed she was having consistent tie-ups,” said Alexia. “They could see that, like, a few days prior, she had had an episode, but she was just standing in the field. I think she was having them more often than we realized.”

MFM is not typically fatal, but many horses don’t return to being ridden. Wilde’s case has been managed by lifestyle, diet and medication. The Honeggers often have days-long drives to get to horse shows from their Colorado base, including this year’s NAYC, so they schedule more layover stops than usual to allow Wilde to get off the trailer and move.

While Wilde’s prognosis was guarded, she returned to work over the winter. She and Haley competed at the National Western Stock Show (Colorado) in January.

It was an emotional moment for the Honeggers, who enjoy participating in the stock show’s kick-off parade down a main street in Denver. Wilde is level-headed enough to be ridden in the parade, following a herd of longhorn cattle.

“She’s the only horse that does the grand prix and walks down the parade,” Alexia said. “It’s a crazy parade, but we always ride—that’s kind of our thing.“

Haley entered her in a gambler’s choice class at the show to test out the mare’s progress over smaller jumps.

“It was really nice because they explained what happened to her and her story, and how she shouldn’t have come back, and she is coming back,” Alexia recalled. “The crowd got really behind Wilde, and it was a nice moment. And they interviewed Haley after she rode.”

Heading into this week’s NAYC, Haley is hoping for a strong finish with her “heart horse,” and Alexia is thrilled to see them both back in the ring. The family heads to Ocala, Florida, next where they’re relocating and starting over with a much smaller program.

“This will be my last time with zone 8—sad to say, but I’m excited, and I feel like we have a really strong team walking in,” Haley said. “I’m hoping we can place on the podium for team and hopefully be somewhere in the top for individual.”

The USET Foundation Performance Pathways Grant she received will help offset costs associated with transportation, entry fees, accommodations and related expenses for this year’s NAYC.

“I’m very, very grateful they were able to choose me, and it means a lot to me,” Haley said. “I get to go compete with Wilde this year at NAYC, and hopefully I can represent really well. It’s special moment for me, for sure.”

Do you know a horse or rider who returned to the competition ring after what should have been a life-threatening or career-ending injury or illness? Email Kimberly at kloushin@coth.com with their story.

The post Wilde Hilde Survives Two Severe Setbacks On Her Way To NAYC appeared first on The Chronicle of the Horse.

]]>The post Eventer Perseveres Through Deadly Cascade Of Colitis Complications appeared first on The Chronicle of the Horse.

]]>That is how EPA Elegance (Wido—Miss Courcel, Dow Jones Courcel) and her owner Shannon Daily ended up with a cheering section, complete with handmade signs, when they crossed the finish line as winners in the training/novice division at the Calais Horse Trials, held Nov. 23 in Powhatan, Virginia.

The event marked the end of a year-long nightmare that “Hazel” almost didn’t survive.

Daily is the first to admit that Hazel, now 8, was very much a “COVID impulse purchase” from the 2021 Goresbridge “Go For Gold” Select Event Horse Sale. Daily grew up riding hunters and jumpers at Level Green Riding School in Powhatan and has since transitioned to eventing. She rode an off-track Thoroughbred for several years and had come to the reluctant conclusion they weren’t well-suited. Because of the pandemic, when she decided to buy Hazel, she had to rely on a network of experts on the ground to vet the mare and crossed her fingers the chemistry would be there.

Hazel went to Leslie Lamb for evaluation and early training, and Lamb suggested they point toward the Dutta Corp. USEA Young Event Horse East Coast Championships (Maryland) in the fall of 2022 where they were 33rd out of 53 in the 5-year-old championship.

“She wasn’t that broke on the flat at first, which I think is kind of typical, so she took a little work there, but as far as the jumps go, she’s always been super game,” Lamb said. “She really came around. She went to the Young Event Horse [Championships], and it was kind of a push to get her there, but we were really proud of her.”

Daily began competing her in 2023, starting at novice and quickly progressing to training as the pair got to know each other.

“She was so great, just a pleasure to ride,” Daily said. “We went kind of all over, and it was one of those things where every event we kept getting better, but we were always one mistake away from winning.

“Our last show of the season was in November 2023 at the Virginia Horse Center Trials. She was just amazing, so fun, and we had a great cross-country run,” she continued.

About a week after the show, Daily noticed a small puncture wound on Hazel’s leg. It didn’t seem deep, but its proximity to Hazel’s knee made Daily nervous, so she consulted her veterinarians at Woodside Equine Clinic in Ashland, Virginia. The surgery team there agreed it would be safest to give Hazel a few days’ worth of antibiotics to stave off infection. Before giving the medication, Daily’s veterinarian warned her about the possibility of rare complications, including colitis. The treatment started on a Thursday.

“On Saturday night, she was totally fine,” Daily recalled. “On Sunday morning, she was so sick. I don’t know if this is a blessing or a curse, but my former horse Oliver had colitis before too, though it was unrelated to antibiotics. I knew what it was. I didn’t even call the vet first; I threw her on the trailer, started driving, and called from the road.

“If you read the scientific research on [antibiotic-induced] colitis, it’s not that promising,” she continued. “They talk about horses dropping dead within a few hours.”

Hazel spiked a high temperature, lost her appetite, and had diarrhea when she was first admitted to the isolation unit at Woodside. Fevers and weight loss would become part of a four-month process of intermittent hospitalizations at Woodside and later the Marion duPont Scott Equine Medical Center in Leesburg, Virginia.

Colitis is usually treated with antibiotics, but Hazel’s veterinary team proceeded cautiously each time they switched to a new one out of concern she might have another negative reaction. Her fevers remained stubborn. Her illness resulted in her developing endotoxemia and septicemia, and then she got thrombophlebitis, swelling and clotting in the veins secondary to the intravenous catheters necessary for her antibiotics. Because Hazel had had a number of catheters in her jugular, veterinarians were concerned that in addition to the danger of clots, they could shelter bacteria in a horse already struggling with a bacterial infection.

One particularly nasty clot on the right side of Hazel’s neck had to be surgically removed and part of the vein tied off. Blood flow is able to continue as normal on the left side, explained Charlene Noll, MSME, DVM, DACVS of Woodside Equine, but it was one more complication.

Additional circulatory issues and continued fevers necessitated a trip to the Marion duPont Scott Equine Medical Center, where veterinarians weren’t optimistic. She was diagnosed with disseminated intravascular coagulation, a rare clotting condition in which blood clots develop throughout the bloodstream.

“They call it ‘death is coming’ because most anybody who gets that, and it happens in humans too, does not survive,” Daily said.

A case of pneumonia and necrotic rhinitis (a fungal disease that ate away at part of her nasal bone) required a tracheostomy, all as the internal medicine specialists called colleagues around the country, brainstorming.

Daily continually asked herself and the professionals around her: Is this fair to the horse?

“Everybody said, ‘We’ll let you know when we don’t think it’s fair, but she’s bright; she clearly enjoys interactions with humans,’ ” Daily said. “Even when she wasn’t eating, even when she had a horrible fever [her temperature hit 107 degrees at one point] she always brightened when people came into the stall. I felt like, in good conscience, I had to give her a chance. If she was going to fight, I needed to fight as well. So we did.”

It was emotionally exhausting. Every day, Daily worried, could be Hazel’s last. But she also knew Hazel was the horse whose stall the technicians would linger in, with her head on their laps while she snoozed. Her name on the feed board had pink hearts drawn around it at Woodside. As awful as the winter was, Daily felt she and Hazel weren’t going through it alone.

As the internal medicine team tried different antibiotics, Hazel’s pneumonia cleared. Her feet, which had been iced throughout much of her hospitalizations, remained cool and sound. Ultrasounds of her heart remained normal. Her bloodwork improved slowly. Finally, it was a penicillin drip that kicked the last of the infection.

In February, Hazel was discharged to a rehabilitation facility, mostly fever-free but weighing 300 to 400 pounds less than she had before her illness. No one knew quite what to expect—whether she could regain the weight, whether she’d tolerate exertion or heat. When she started galloping in her field, playing with a fellow patient across the pasture fence, Daily felt glimmers of hope.

The pair resumed light work with Lamb this spring, and other than what Daily describes as a “Darth Vader sound” when she canters due to her nasal bone changes, Hazel is healthy, sound and apparently no worse for wear.

The Irish Sport Horse can be on the lazy side—the type of horse who jumps better when the fences get bigger because of how capable she is. Despite their preparation at home and at a cross-country school, Daily admitted to being a little nervous going into the grass arena at Calais to do the training-size stadium round. It was immediately clear as they progressed that Hazel was back and, if anything, “a bit saucy.”

“When we landed from the last jump and I could hear everybody cheer us on, saying ‘Go Hazel!’ and seeing my family there, that really moved me,” Daily said.

They crossed the finish flags in the cross-country almost exactly a year from the day Hazel first fell ill. Some of her fans made the trip from Woodside to cheer her on, and Noll said Hazel updates are part of the clinic’s Slack channel.

“She’s always a friendly and positive horse, easy to work with, and just a really pleasant individual,” Noll said. “She seems to be able to do her job and do it well. It’s on to regularly scheduled events.”

Daily is hopeful that may include a move up to modified and perhaps a run at preliminary one day. Whatever comes, she has no regrets about the fight for Hazel’s life.

Do you know a horse or rider who returned to the competition ring after what should have been a life-threatening or career-ending injury or illness? Email Kimberly at kloushin@coth.com with their story.

The post Eventer Perseveres Through Deadly Cascade Of Colitis Complications appeared first on The Chronicle of the Horse.

]]>The post Back From The Brink: After An ‘Unsurvivable’ TBI, Emily Brollier Curtis Sees Life Differently appeared first on The Chronicle of the Horse.

]]>Emily Brollier Curtis isn’t quite sure what happened on Jan. 19, 2024.

The professional dressage trainer was hacking a horse after an uneventful schooling session at her Florida winter base before her assistant, MacKenzie Wood, found her 40 feet away from the barn, on the ground with no visible injuries. Wood checked Curtis over briefly as the rider sat up and took off her helmet, assumed she just got the wind knocked out of her and quickly took her horse back to the barn. She returned to find Curtis unresponsive and not breathing, and she began to administer cardio-pulmonary resuscitation. What followed was a harrowing month that changed Curtis’ life and riding career forever.

“Me being able to talk to you, there is no other word—it’s miraculous,” she said. “I’m a pretty faith-based person. I do think there’s no other word for it than miracle. I’m thankful for that, because the best medicine in the world can’t explain why I’m OK.”

Curtis was diagnosed with what she was told was an “unsurvivable” brain injury, displaced fractures of her C1 and C2 vertebrae, as well as some broken ribs.

She’d been known as someone who could ride just about any horse and took on some of the toughest ones, rarely coming off—though the horse she fell from was considered a safe one. She always wore a helmet.

“It’s a wonderful example of, accidents happen,” she said. “My neurosurgeon said, based on my injuries, he thinks I was unconscious before I hit the ground. Whether the horse stumbled and stunned me and hit the brim of my helmet, or I passed out—I’ve never passed out before. I had zero defensive wounds. I know how to fall.”

Intubated and airlifted to St. Mary’s Medical Center in West Palm Beach, Florida, she underwent an emergency craniotomy less than an hour after her fall to relieve bleeding and pressure in her brain. She had a 9-millimeter midline shift of her brain, and was told a “significant” shift was anything over 5 millimeters. Anything over 7 millimeters was not often survivable. Combined with neck fractures that left a small piece of bone sitting right next to her spine, there was a possibility of her being paralyzed or unable to speak if she woke up.

“They said they see this kind of injury in head-on collisions going 80” miles per hour, she said. “I’ve been over it a billion times, what could have happened to me. And my helmet doesn’t even have a scratch on it. It’s the most bizarre thing. It was so bizarre that they taped off the farm as a crime scene because they assumed I was dying. I had a less than 1 percent probability to survive through that first night.”

It was a terrifying prospect to her family, employees and her husband, Aaron Curtis, who flew in from their Nicholasville, Kentucky, home with their 2-year-old daughter Olive Curtis.

Doctors kept Emily in an induced coma, where she spent two weeks before she started making movements, giving them hope that she wasn’t paralyzed.

“As I’m coming awake and finally wrapping my head around what happened to me, I asked my husband,” she recalled. “He said I fell off a horse and hit my head. I just looked at him and said, ‘No, that can’t be right.’ They started to determine I was going to be verbal, and by the time I left critical care, they looked at my husband and said, ‘I think she’s going to make a full recovery.’ ”

Three weeks after the fall, Emily was flown to the Shepherd Center in Atlanta, which works with brain and spinal-cord injury patients. She and her husband were told to expect a long stay, but six days later, she was discharged because she was “too high-functioning.”

But it would still be a long road to recovery. Emily started attending occupational and speech therapy in Kentucky as her neck fractures healed. Before the accident, she was extremely fit, running 30-40 miles each week, riding 10 horses, teaching and going to the gym.

Meanwhile, her team at her Miramonte Equine took over riding her horses and her clients’ horses and running the business.

It took some time for her speech cadence to come back, but as soon as she was able to form sentences, she called her friend and mentor Jim Koford and asked him to take on the ride of her horse, Secret Royal 3. She’d only purchased the 6-year-old Oldenburg gelding (Secret—Luna) in December 2023 and knew he was special.

“I bought myself that horse of a lifetime, and then promptly broke my neck and went into a coma four weeks later. You can’t make that up!” she said with a laugh. “He is incredible. I’m so grateful for Jim to take him. I wanted Jim to put him in all these environments. He’s literally foot perfect. I think a lot of the time you get horses of that quality, but they’re quirky. You couldn’t make a better horse. He’s ungodly athletic and talented, and then he’s so kind.”

Koford said he was shocked to receive a call from Emily, saying it felt like it was coming from the grave. “I couldn’t believe it. She still laughed at my dumb jokes; it was like Emily, not just a shell of Emily. Her speech was a little slower, but it was like, my girl’s back,” he said.

Koford had known Emily for a decade, meeting her back when he was living in Kentucky. He knew she would fight her hardest to get back on a horse after her injury.

“She had this old Thoroughbred, and somehow, she had kicked, scratched, crawled her way all the way up to Grand Prix,” Koford recalled of his friend and her natural perseverance. “I was watching her ride around, and the horse had no innate talent and wasn’t terribly cooperative. Somehow by sheer will and tenacity, she just got it done. She was scrappy and tough.

“Emily is such a vibrant, happy, athletic, positive person,” he said. “She’s been hit with some of the toughest scenarios, and she just always comes out of it with smiles. Takes a lickin’ and keeps on tickin’. It’s just amazing, her resilience. But this one I thought, man. It was horrible. You just have to sit and wait. It’s brutal watching it from the side.”

Emily spent 2024 working hard in speech therapy and, more recently, physical therapy for her neck. In the meantime she’s enjoyed watching Koford bring “Roy” along at third level. He rode the gelding in the 6-year-old championship at the U.S. Dressage Festival of Champions (Illinois) in August, and they went on to win the open third level championship at the U.S. Dressage Finals (Kentucky) in November.

“Part of my speech therapy was going back through my text messages to try to recall whatever I could recall, and I see all these messages to Jim,” Emily said. “I was obsessed with this horse. I kept telling him how amazing this horse was.”

Emily was teaching lessons just a few weeks after her initial rehab, and in the past month she’s been given the go-ahead by her doctors to resume regular day-to-day activities, including running.

“I have said over and over again that pressure is a privilege,” she said. “This morning—at a real feel of 2 degrees—I went for a run. It’s so liberating. Everything’s a gift to me right now. I don’t care how cold it is, I’m doing a mile.”

She also got the “courage” to ask her neurosurgeon about riding again.

“He said there’s always going to be a risk because riding is risky in general,” she said. “He said, ‘Yeah, you can ride, just don’t fall off ever again.’ I said, ‘Yeah, OK!’ He said head injuries are cumulative, and mine was the mother of all head injuries.

“It’s going to look very different for me,” she continued. “Before I would ride almost anything, so riding for me is going to be horses I know, and my staff will have to ride them first when I get a new one to make sure it’s something I can ride. I have to mitigate all risks possible.”

In November she got back on a horse for the first time since her accident, picking an older, trusted horse, Thaddeus.

“I rode him the day I had my baby and through my pregnancy,” she said. “He loves me, and I love him, and I think he knows that. He’s not a deadhead. He’s pretty sensitive and pretty go-ey, but he’s so kind to me, and he will never ever be for sale.

“Like everything with my injury, everything has escalated quickly,” she added. “I started with MacKenzie just handwalking me around the arena, and it felt fine, so the next week I said, ‘I think I can trot!’ It felt fine. My neck was tired from holding my helmet up, but it gets stronger every day. The next week I said, ‘You know, I think I can canter.’ This week I did five flying changes on a diagonal. My body knows what to do. It feels so wild. I’ll feel my horse get a little crooked, and I know exactly how to straighten him.”

Life in Emily’s world can be chaotic—with students, a toddler and many horses, she wasn’t exactly able to avoid loud noises and a low-stress environment as prescribed—but overall she says many of the things she was warned about with brain injuries haven’t come true yet.

“Brain injuries are insane, and you don’t really know what you’re going to get,” she said. “Time is the biggest factor to tell you what you’re going to be able to do. Mine is classified non-survivable. My long-term memories are gone, which is kind of sad. I knew I had a kid, but my context is gone. I know who my husband is, and my facial recognition is pretty good, but I don’t have any memories of dating him or my wedding. It’s kind of sad, but if that’s the worst thing I have, it’s OK.

“I can’t remember a ride on a horse, but my body knows how to ride a horse, so I can teach,” she added. “It’s super strange. I know people don’t quite grasp how much of my memory is gone—because [of my] cognition I’m really sharp, and my speech is almost 100 percent normal again. Problem-solving, retention and short-term memory are all great. I can make new ones, so that’s OK.”

Emily is hoping to take the ride back on Roy in time, but for now she’s enjoying her life, even though it’s been changed forever.

“I’m just grateful,” she said. “I’m grateful for everything, I’m grateful for my faith, the neurosurgeons, MacKenzie. The circumstances couldn’t have turned out better, but I’m also surrounded by some of the best people I could be in that situation.

“It’s changed my life, but I think it’s for the better,” she added. “It’s made me appreciate things that I probably took for granted before, and I think it’s going to make me a better rider because it’s going to allow me to focus on better horses and not be so distracted with trying to fix problems of horses I have no business riding. In the long run, I still get to do everything that makes me, me. My personality is still 100 percent the same, good, bad or ugly. It’s such a strange outcome. I think it will make my career better.”

Her close friends and family are both profoundly grateful for her recovery thus far, and protective of her health.

“One of the scariest things for her husband, her friends and myself is watching her ride again, but I think we’re all protective and making sure she can ride, be supported, and only on the best horses,” Koford said. “Roy will be a part of that when she’s ready.

“It’s really a lesson to all of us,” he continued. “To see someone who’s been hit with such adversity stay so positive—especially people with head trauma. It’s horrible watching people that have been through that and deal with depression and anger and rage. At least outwardly, she’s good! She puts a smile on her face, and it’s a three-ring circus at her place. There’s kids and teenagers and adults and the horses in and out. It’s just always something, and she’s at the center of it all. It’s kind of hilarious, this amazing, positive energy. And she’s surrounded by the most amazing husband and child and staff. She’s blessed with an amazing barn family.”

Do you know a horse or rider who returned to the competition ring after what should have been a life-threatening or career-ending injury or illness? Email Kimberly at kloushin@coth.com with their story.

The post Back From The Brink: After An ‘Unsurvivable’ TBI, Emily Brollier Curtis Sees Life Differently appeared first on The Chronicle of the Horse.

]]>The post Emma Hechtman Rebounds From Fractured Pelvis To Eq Finals appeared first on The Chronicle of the Horse.

]]>After trotting around a few times on the next horse, Emma gently asked the mare to lengthen her stride.

“Suddenly the mare tripped and went down on her right shoulder. I went down with her and broke my fall with my right shoulder,” said Emma, who was wearing an air vest at the time. “Then the mare somersaulted, and part of her body landed on my side, which was directly on my pelvis. I was running on adrenaline at the time, so initially, as I laid on the ground, I didn’t feel anything.”

But when Emma tried to stand, something was horribly wrong.

“I realized that I couldn’t move, which was a scary feeling,” she said. “I remember yelling out to someone to grab the horse and saying that I needed help. A bunch of people ran over; I don’t remember seeing their faces.”

Within minutes, her mother and trainers from Heritage Farm—Andre Dignelli, Patricia Griffith and Laena Romond—arrived.

“I had never seen Andre so scared before,” Emma said. “And that’s one thing that really scared me, because I remember looking over and seeing him and Laena—their faces were white. And I remember thinking to myself, ‘OK, this is not good. What is wrong?’ ”

Paramedics determined Emma did not have a concussion, then evaluated her for broken bones.

“I had to reassure everyone that my head was fine, and I had not hit it during the fall,” Emma said. “I was cracking jokes the entire time with the paramedics. They knew I had broken something and that I needed to go to hospital. I ended up finding out at the hospital that I had won the low junior jumper class that morning, too.”

Emma was whisked off to Albany Medical Center (New York), a Level 1 trauma center, where her medical team determined she had a bilateral pubic rami fracture, a left sacral alla fracture in her pelvis, and a fractured and displaced collarbone.

A few days later, Emma flew back to Florida, where her orthopedic surgeon Dr. Nicholas Sama used a plate and eight screws to repair Emma’s fractured collarbone. Sama estimated her collarbone would take four to six weeks to heal, and her pelvis, which did not require surgery, would take eight weeks.

The recovery window dashed Emma’s summer horse showing plans. Even more, she was worried about making it to the fall equitation finals, which loomed on the horizon.

“My eight-week mark was right when Zone 2 ASPCA Maclay Regionals were,” Emma said.

Prior to her injuries, Emma had qualified for almost all of the fall 3’6″ equitation finals.

“For me, the thing that hurt the most mentally was that I had gotten so far in my riding, and I wasn’t ready for the summer to end,” she said. “I was so happy where I was.”

As Emma tried to navigate her new normal, Dignelli offered encouragement.

“I said, take a breath,” he recalled. “It all seems catastrophic right now, but the body has a way of healing itself, and let’s not get ahead of ourselves.”

While Emma began her recovery, the Heritage team kept Kingsroad, her equitation horse, fit on the off chance she could recover enough to compete.

“I wanted to be prepared either way,” Dignelli said. “Had we not had the right horse for Emma, we may have felt differently [about this plan]. But we had a horse we trusted for her, and we felt confident in his abilities. We wanted to make this happen for her.”

Determined to make it to the equitation finals, Emma turned her full attention to her rehabilitation.

“I couldn’t walk correctly for a long time, because when I tried to walk correctly, I had radiating pain down my body [from my pelvis],” Emma said. “So I had to relearn how to walk in physical therapy; I had to strengthen my right shoulder again, and I basically had to do that in three weeks’ time before I went to Oklahoma State University.”

Because of Emma’s collarbone surgery, she could not use a cane or walker to support her during recovery. While she could walk short spurts at home, she needed a wheelchair for long distances.

Three weeks after Emma’s surgery, she made it to move-in day at OSU in Stillwater. Many of her National Collegiate Equestrian Association teammates helped her move her things into her dorm and get settled. She couldn’t participate in any workouts or riding for several weeks, but the school’s athletic trainer, Erin Simmerman, and sports medicine doctor, Dr. Jason Moore, took charge of her rehab.

“They helped guide me through my recovery—they all rallied behind me to help me get to regionals,” Emma said. “The support from everyone at OSU—my NCEA coaches Larry Sanchez, Carter Anderson and Alle Durkin and my teammates—and my trainers at Heritage was absolutely incredible.”

By the six-week mark, Emma was able to flat a horse at OSU for the first time and by week eight, she was back in New York at the Old Salem Horse Show for Maclay regionals. Griffith, who had the same collarbone surgery in September 2023, remembers telling Emma to pace herself as she started riding again, knowing she might tire faster.

“You do have to push yourself a little bit—you don’t want to be reckless, but you do have to relearn it,” said Griffith. “[At first] you think, am I ever going to be OK? And then one day you just are. I told Emma to rest for a minute, but to not be afraid after her surgery to push herself a little bit. You have to strength train to get back to yourself. She slowly pushed herself and did a little more each time.”

“I didn’t get full strength back for a while,” Emma said. “[At first], when I would go to put my left leg on [the horse]—that’s where my biggest fracture was—there was no power. The horse wouldn’t move off of it; there was no strength there. That was pretty frustrating.”

Nonetheless, Emma placed sixth at regionals with Kingsroad, earning them a trip to the ASPCA Maclay Final at the National Horse Show (Kentucky).

It was especially gratifying because “Roady,” an 11-year-old Holsteiner gelding (Kannan—Monata) owned by Elin Uppling, had also spent part of the summer recovering from a mild injury.

“Everyone at the barn was calling us ‘the Comeback Kids,’ ” Emma said. “It was really exciting to get a ribbon [at regionals]. I couldn’t have done it without all of the support I had from everyone.”

With their successful trip to regionals, the “Comeback Kids” were on the road to the fall equitation finals that Emma once worried had vaporized after her accident.

They first competed in the equitation at Capital Challenge (Maryland), then headed to the Dover Saddlery/USEF Hunter Seat Medal Final at the Pennsylvania National. There, she had a great trip and made one of the stand-by lists, but a swap ultimately kept her out of the second round.

Three weeks later, they were in Kentucky for the National Horse Show and her first Maclay Final. While similar problems kept them out of the stand-by there, Emma was happy with their performance.

“Both Roady and I had never done [the 3’6”] equitation finals before, so being able to go, even after the accident, was such a huge accomplishment,” she said. “Andre was happy; I was happy; it all worked out.”

Thinking back on the accident, Emma is grateful to her father, Jason Hechtman, who is a breast cancer surgeon, for teaching her how to properly fall off of a horse at a young age.

“I’m 5’2” on a good day now, so I was really tiny as a kid,” Emma said. “When I first started riding, my dad was really nervous about me getting hurt when I fell off. As a doctor, my dad is also trauma trained. He taught me to brace with my shoulder on impact so I would protect [the rest of my body], because your shoulder can take the brunt of the fall. I unconsciously fall that way now, and I think that’s one thing that saved me in my accident this time.”

Throughout Emma’s recovery, the Heritage team admired her determination and dedication.

“When things don’t go right, which is over 50% of the time with horses, she’s able to process and learn from it,” Griffith said. “And Emma was able to do the same thing with her accident: put it behind her and keep moving forward. Sometimes with an injury, you get set back mentally. But Emma was not that way—she was ready to keep moving forward and make it happen. And that’s what helped her succeed.”

Do you know a horse or rider who returned to the competition ring after what should have been a life-threatening or career-ending injury or illness? Email Kimberly at kloushin@coth.com with their story.

The post Emma Hechtman Rebounds From Fractured Pelvis To Eq Finals appeared first on The Chronicle of the Horse.

]]>The post Thanks To A New Surgical Procedure, Rock Phantom Is Back On Course appeared first on The Chronicle of the Horse.

]]>“Honestly, when Nilson rung me about the horse, I didn’t think of him for myself—I didn’t think I was going to be able to raise the money to buy a horse like that,” said Kozumplik, who divides her time between Berryville, Virginia, and Ocala, Florida.

So Kozumplik shared the information with several friends who were in the market. But when none of them seemed overly interested in purchasing the gelding, she decided to try “Rocky” herself and clicked with him immediately. She talked to her longtime supporter Edy Rameika, and she was enthusiastic about coming on board.

“I wasn’t thinking at that particular moment of my life that I was going to try to take on that next thing,” said Kozumplik, who was finalizing a divorce at the time. “But Edy has been my main owner for nearly 25 years, and she said, ‘We need a horse to be out there and get back into this a bit.’ We were starting a few things fresh, and he was part of that.”

Rocky and Kozumplik made their competitive debut in late January 2022, running preliminary at Grand Oaks (Florida) before moving up to intermediate at Rocking Horse (Florida) the next month. Rocky’s weakest phase was show jumping, so Kozumplik also took advantage of jumper classes in open shows to strengthen his skills. In August, the pair made their CCI3*-S debut at Great Meadow International (Virginia), and the following month, finished seventh in the CCI4*-S at Stable View in South Carolina.

“The horse was being really good, and as I got to know him better, I had some good early results on him,” Kozumplik said. “Things were getting better and better, especially with his show jumping, and then about a year ago, he took a step back, and I couldn’t figure out why.”

Although the pair continued to experience competitive success in 2023—including a 15th-placed finish at the Cosequin Lexington CCI4*-S (Kentucky) and winning the Chattahoochee Hills CCI4*-S (Georgia) in October—as the season progressed, a few new issues began to emerge. First, Rocky started pushing harder into Kozumplik’s left leg than he had before, particularly when asked to rebalance from the gallop. Initially, he had been stiffer on his right side, but now, he was stiffer left. Occasionally, Rocky was a little slower with his left foreleg than his right in the air over a fence. And then there was the tripping—as long as she’d known him, whenever Rocky stumbled or took a stabby step, he would bolt forward.

“These are all things that ended up being symptoms,” Kozumplik said. “It happened progressively over time, where I didn’t notice it as much as I should have.”

Kozumplik turned to Jonathan Furlong, DVM, MSEd, of B.W. Furlong and Associates in Oldwick, New Jersey, for advice. Initially, they wondered if Rocky’s back was bothering him, but Furlong couldn’t isolate a problem; a lameness exam turned up nothing unusual. Ultimately, Furlong took several standing cervical radiographs and determined Rocky might have an area of compression between the C6 and C7 vertebrae in his neck. But overall, nothing definitive emerged, and with the support of her veterinary team, Kozumplik continued pursuing her training and competitive goals.

Then, at the Setters’ Run Farm Carolina International CCI4*-S in March 2024, Rocky and Kozumplik had a bizarre fall. Toward the end of what had been a solid cross-country run, she remembers seeing a good line and giving Rocky a positive ride to a brush fence into the final water complex. The next thing she knew, Kozumplik was out of the saddle and soaked, and her horse was scrambling to maintain his footing.

“He actually stayed on his feet, I don’t know how,” Kozumplik said. “I didn’t know what had happened—99.99% of the time when I have had a horse fall or almost fall, I know what went wrong. There has only been twice where it happened and I had no idea why, and one of those was at Carolina.”

Afterward, a friend shared a video filmed from the front—and Kozumplik could see just how badly Rocky had hung his left front leg at the fence. She sent the video to two trusted friends and five-star colleagues, Lynn Symansky and Hannah Sue Hollberg, and asked what they thought.

“We are so lucky in this sport to have a lot of good relationships, and they are both really good at this type of thing, to determine if a problem is veterinary or technical,” Kozumplik said. “And Lynn said to me, ‘He is really pushing into your left leg.’ She could see that in the video—and told me I should do a [computed tomography] scan of his neck.”

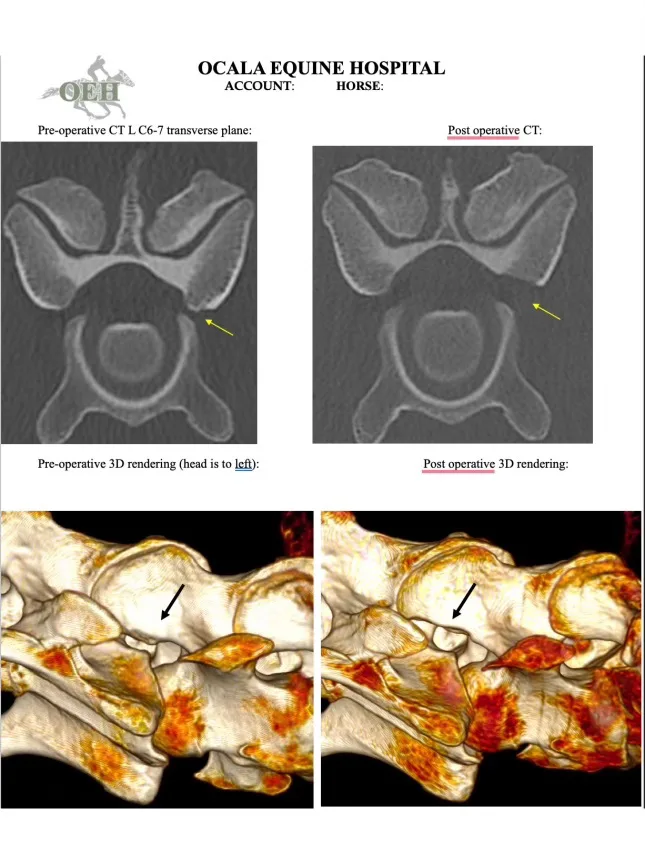

The week after Carolina, Furlong referred Rocky to the team at Ocala Equine Hospital, where Travis Tull, DVM, DACVS, consulted. After Rocky’s CT scan—which gives a comprehensive 3-D view—Tull confirmed Furlong’s initial suspicion. Rocky was indeed experiencing compression in one area where his spinal nerves exit the spinal column, resulting in cervical radiculopathy. In layman’s terms, Rocky had a pinched nerve in his neck that was likely causing pain and interfering with the mobility of his left foreleg.

“The most common cause in horses is an enlarged articular process joint, which are paired joints between the vertebrae on either side of the spinal canal,” Tull explained. “The enlargement can cause a narrowing of the opening where the cervical spinal nerve travels to relay information to and from the spinal cord.”

Historically, initial treatment options for horses with the condition focus on a combination of physiotherapy and medical support; in Rocky’s case, Furlong performed an ultrasound-guided corticosteroid injection into the joint. When Kozumplik brought Rocky back to work post-injection, she immediately noticed an improvement in his way of going. As a test, she re-created the type of jump he had struggled with at Carolina, and she noted he used his left forelimb “completely differently.”

With the 2024 Defender Kentucky CCI5*-L still on their calendar, Kozumplik took Rocky to one final horse trial as a prep and status assessment. Not only did Rocky feel better, he won his intermediate division; after consulting with her veterinary team and Rameika, Kozumplik decided to press onward to Kentucky.

“Everyone was really excited; the horse felt a lot better, and he had the miles—I decided to go,” Kozumplik remembered. “But this was in the back of my mind: If this horse goes out there, and he’s not jumping well, then I’m pulling up.”

Despite a solid warm-up, Kozumplik sensed almost from the moment Rocky came out of the start box in Kentucky that he wasn’t in top form. When Rocky refused the first water at Fence 5, Kozumplik put her hand up and called it a day.

“I don’t know. It could have been a bit mental on my part, because I knew he had this issue,” she said. “He is such a sweet, kind horse, and when he stopped at the water, I just thought, ‘Absolutely not.’ ”

During Rocky’s assessment at Ocala Equine, an additional treatment option had been presented—a newer procedure called a percutaneous single portal endoscopic foraminotomy. Pioneered by German veterinarian Dr. Jan-Hein Swagemakers in 2020, in a foraminotomy, surgeons insert a specialized endoscope alongside the affected articular process joint through a small incision in the skin, then use various tools to remove the excess bone, create more space and reduce pinching of the nerve. Horses tend to do well following the procedure; rehabilitation begins just three days later, and most are back in ridden work after six weeks.

Kozumplik said the decision to do the foraminotomy was “a bit of a no-brainer.”

“Regardless of what he would come back to do, I knew it would make his quality of life better,” she said.

Rocky’s connections knew the gelding would be in capable hands with Tull. In August 2023, Tull had performed the first foraminotomy in the United States; since then, he has taught 18 other veterinarians how to do the procedure. Ocala Equine is one of just eight hospitals nationwide currently offering foraminotomy, but Tull said its availability has improved the possible outcomes for horses experiencing cervical radiculopathy.

“Before the advent of foraminotomy, the only options were medical treatment or cervical spinal fusion,” he said. “After foraminotomy surgery, horses are rehabilitated to improve their mobility, proprioception and core muscular strength.”

Rocky’s surgery was performed just after Kentucky in early May, and despite being five-star fit at the time, his sensible nature made him a good patient. He was back in the field as soon as possible post-surgery, and immediately began his unmounted rehabilitation work that included walking on uneven surfaces, walking up and down small hills and going on and off blocks.

In hindsight, Kozumplik realized that Rocky had often struggled with undulating and uneven surfaces. As he worked through his recovery protocol, the issue resolved, and Kozumplik also noticed Rocky became more supple over his topline.

“Before his surgery, he would get tight in the canter, both in the dressage and a bit in the jumping,” she said. “And of course, there was his reaction to getting stabby or tripping. All of that went away.”

By mid-summer, Rocky was back in full work, and Kozumplik made a plan to return him to competition. After a successful run at preliminary late in July, she entered him in the intermediate at the USEA American Eventing Championships, held at the Kentucky Horse Park in August.

“Intermediate is a level that is quite easy for him, and I thought running through those waters in Kentucky would give him a lot of confidence,” she said. “It’s big enough but not too hard, and I thought we would see where we are.”

Despite the heat that week, Rocky felt solid on cross-country, only tiring slightly at the end of the course, and he wasn’t leaning into Kozumplik’s left leg. But it was perhaps his show jumping performance the next day that proved the most informative.

“He felt weak, almost like his left side was atrophied,” Kozumplik recalled. “He has a big heart, and he tried his guts out—and I had more information.

“I wanted to test him at the four-star level before I gave him a break for winter, but after AEC, I knew he was not strong enough,” she continued. “He needed to do more at the three-star level.”

She entered Rocky in three-star competitions held at Plantation Field (Pennsylvania) in September and Morven Park (Virginia) in October. Kozumplik focused on giving Rocky a positive ride and adding more speed—and at Morven, with a clean show jumping round, they won. After those successful runs, Kozumplik decided Rocky was ready to return to the four-star level. And at the Bouckaert Equestrian International (Georgia) in late October, he did so with style—delivering three solid phases to finish first.

It was there that Kozumplik knew she truly had her horse back.

“There were some fairly big rails into the last water, and I didn’t get a great ride into it,” she said. “I missed a bit, but he was very good and made up for it. It made me believe that he feels much better.”

The Bouckaert International is the second qualifier in the new US Equestrian Open series, which offers significant prize money and will culminate in a championship final next fall at Morven Park. Kozumplik thinks the series will suit the 13-year-old gelding well, and she plans to focus on those events with a goal of contesting the final.

“If he does that well, then I’ll bring him to Kentucky the spring after that,” she said. “But honestly, if the horse never does a five-star, I’m OK with that, too. If he’s happy at the four-star level, I’m fine with that. He’s a really nice horse.”

Do you know a horse or rider who returned to the competition ring after what should have been a life-threatening or career-ending injury or illness? Email Kimberly at kloushin@coth.com with their story.

The post Thanks To A New Surgical Procedure, Rock Phantom Is Back On Course appeared first on The Chronicle of the Horse.

]]>The post Tufton Avenue Makes A Winning Comeback appeared first on The Chronicle of the Horse.

]]>Stephanie Danhakl remembers her 35th birthday well, and not just because it was the first one she was celebrating after giving birth to her son, Miles Raymond. Instead, the date—Jan. 26, 2022—is seared in her memory because of a phone call from her veterinarian.

“I was at the table, my parents were in town because they were visiting the new baby, and the vet called me and said, ‘I’m sorry, Stephanie, but you need to put your horse down,’ ” she recalled. “And I just—there were so many emotions going on at that time, and I said, ‘What do you mean? He’s supposed to be ready. He’s supposed to be almost healed from this. What happened?’ ”

Back in August 2021, at Danhakl’s final show during her pregnancy, her horse Tufton Avenue was injured. “Tuffy” was diagnosed with a fractured coffin bone and torn impar ligament. While it sounded serious, Danhakl was reassured that in six months to a year, he’d be back to himself. Her veterinary team predicted he’d be ready to resume work around the same time Danhakl would get back in the tack.

But instead, the veterinarian was calling to say that due to degeneration of the navicular bone, Tuffy risked a more serious injury to that leg if he took a bad step, and he recommended euthanasia. It was a tough blow for Danhakl, who’d unexpectedly lost another of her show horses, Enough Said, to a cardiac event in the pasture on Jan. 1. Now she was facing another painful loss.

After getting reassurances that his condition wouldn’t deteriorate so much in a few days that it was unwise to wait until she could book a trip down to Wellington, Florida, from Boston, Danhakl made plans to travel and say goodbye to the horse.

Within a week, she’d arrived at Rivers Edge Farm’s winter base, and when she approached Tuffy’s stall, she was met with a whinny and a bright-eyed expression.

“He turned his head over to me, and he just gave me this look,” she said. “And from that second, I knew that he had life back in him, and I didn’t care what anyone said to me. He was trying to tell me that he wanted to fight, and that he was going to be OK.”

She and her trainer Scott Stewart sought additional veterinary opinions, and a few said that, if she was lucky, they could get the Holsteiner (Spartacus TN—Pialotta VII, Caretino) sound enough to retire comfortably. Jennifer Feiner Groon, VMD, came up with a game plan to rehab Tuffy: In addition to the platelet-rich plasma treatments they’d been using to help stimulate healing, Groon wanted to get Tuffy more mobile—but in a controlled setting.

Initially the bay gelding was restricted to short handwalks, but after he’d made progress with that, he graduated to turnout in a medical paddock—heavily supervised because any shenanigans could exacerbate the injury.

Tuffy behaved, and within six months, he had made marked improvement. While not perfectly sound, he was able to trot in the field, and when Rivers Edge migrated back to Flemington, New Jersey, Tuffy was given 24/7 turnout. For the next year he received periodic veterinary examinations to monitor his progress, and those indicated that the affected bones had healed and stabilized.

“We would get these videos of him going nuts in the paddock, bucking huge, rearing, running around, and he would stay sound,” said Danhakl.

With a green light from his veterinary team, Tuffy began an under-saddle rehab plan. As his workload increased, he remained sound. Ever since his initial injury, Danhakl had been wishing for the day she got to sit on him again, so her first ride back was emotional.

“I couldn’t believe it,” she said. “By then actually I’d had another child, so there was all this time that’d passed, but he felt like the same Tuffy.”

A Particular Horse

Danhakl purchased the now-12-year-old gelding in January 2020 from Katie Cooper Curry and Katie Francella. Curry described him as a quirky young horse, the type who would spin away from the in-gate when he was already in the ring, was funny to get on, and who would be difficult to ride after a couple days off.

“I’d just take my time. I’d pet him a lot and try to give him confidence and try to do it his way enough that he would come to the party to do it our way,” Curry said. “So I felt very lucky to have such a special horse, and there were people along the way—people would see him [and say], let me know when he’s ready.”

When it came time to sell him, Curry knew it was going to take the right person to be his next partner. She’d spent a lot of time telling him he was a winner, and Danhakl was the kind of rider who could carry on that work.

“I think she’s got a great team there that can also understand that [you can’t push him] and do what’s needed, and I think that’s been key for his success,” Curry said.

Tuffy caught Stewart’s eye one day when they were both showing in the 3’6″ green division, and he told Danhakl she should try him. At the time, Danhakl was content with the horses she had, but she agreed to sit on him.

“It was an instant connection,” she said. “I think I jumped one jump on each lead, and then I felt comfortable enough. I said, ‘Just put the jumps up to 3’6″; I can jump him around.’ It was like I’d been riding him forever. We just basically bought him on the spot.”

The pair found immediate success, but then the pandemic disrupted the show schedule. Danhakl didn’t get to compete him at the top shows before his injury.

“I never gave up hope. I probably should have, but he was telling me that he still had it in him,” she said. “I still feel like we have a lot of unfinished business, and I want to show the horse world how truly exceptional he is, and that’s really important to me. He just so deserves it. He’s a once-in-a-lifetime horse, really. I just admire him so much and love him so much.”

“I never gave up hope. I probably should have, but he was telling me that he still had it in him.”

Stephanie Danhakl

This February, after two and a half years away, Tuffy returned to the show ring in the adult amateur hunters. When that proved easy, they moved him up to the 3’3″ amateur-owner hunters. They kept his schedule light, but their consistency earned them a trip to Devon (Pennsylvania), where they were reserve champions in the 36 and over section.

While Tuffy still isn’t the most straightforward horse to ride, Danhakl said he feels calmer than he was before the injury.

“You’d have to be very careful around him, because he gets startled easily,” she said. “You have to move slowly. He’s a horse that it takes a very particular person to be around him, because he’s not just ‘go with the flow.’ He’s very particular, and he lets you know right away if there’s something he doesn’t like. And I think the thing about my relationship with him is that he’s the boss, and I’m just there listening to him. We have that kind of relationship where if there’s something he’s not happy with, I’ll just give him time. If he’s spinning around in the corner of the ring, I’ll just say, ‘OK, you can just wait here until you’re ready,’ and then let him go when he’s ready. I never try to push him to do what he doesn’t want to do. And he does it willingly eventually.”

This year, the pair made it to the fall indoor circuit, and they picked up the win in the WCHR 3’3″ Amateur-Owner Challenge at Capital Challenge on Oct. 3 in Upper Marlboro, Maryland, cementing Danhakl’s belief that she truly had her horse back. She gives full credit to the team at Rivers Edge for keeping him fit and sound.

“I’m very fortunate that I have such great care and so many people cheering him on and looking out for him,” she said.

This article originally appeared in the November 2024 issue of The Chronicle of the Horse. You can subscribe and get online access to a digital version and then enjoy a year of The Chronicle of the Horse. If you’re just following COTH online, you’re missing so much great unique content. Each print issue of the Chronicle is full of in-depth competition news, fascinating features, probing looks at issues within the sports of hunter/jumper, eventing and dressage, and stunning photography.

Do you know a horse or rider who returned to the competition ring after what should have been a life-threatening or career-ending injury or illness? Email Kimberly at kloushin@coth.com with their story.

The post Tufton Avenue Makes A Winning Comeback appeared first on The Chronicle of the Horse.

]]>The post A Broken Pelvis And An Unexpected Diagnosis Don’t Stop OTTB Eventer appeared first on The Chronicle of the Horse.

]]>When amateur event rider Lauren Field lost her horse unexpectedly, the longtime Thoroughbred lover knew exactly where to look for her next mount. In 2013, Field reached out to Finger Lakes Finest, a Thoroughbred rehoming organization in New York, to find a suitable match. When her first choice didn’t pan out, Lucinda Finley, founder and on-track coordinator for the organization, directed her toward Midnight Tucker, a tall, plain dark bay that several other adopters hadn’t connected with.

“Lucinda reached out to me, and said, ‘There is this one horse you need to look at, but he’s not flashy, and he’s not personable,’ ” recalled Field, who was looking for an eventer.

Upon meeting the 5-year-old (Say Florida Sandy—Midnight Mood, Talc) gelding, Field’s first impression was of a “miserable, shut down” animal.

“I could see why so many people had passed on him, because there wasn’t that gravitas there,” Field remembered. “He looked so unhappy and seemed a little body sore.”

But she also noticed the horse’s soft eye, and when his handler led “Holden” out of the stall, she was positively impressed.

“His trainer was probably the lamest person I’ve ever seen, with the shortest, most hobbling stride,” said Field, 34. “He takes this strapping, 17-hand, race-fit horse out, and Holden took the tiniest little steps to stay with this man, who could barely jog. He was so gentle. That’s when I realized, ‘This is the one.’ ”

Though Holden had “a bunch of jewelry and some scars,” and seemed slightly off on his left hind, Field skipped the pre-purchase and adopted him. Once home, veterinarians determined that Holden raced on an unhealed collateral ligament injury in his left hind fetlock. Despite showing some signs of remodeling, it was likely the cause of his uneven stride. It was a significant injury, but the fact the horse wasn’t more lame proved to Field that Holden was both tough and stoic.

After six months of rest, Holden was given the green light to work. Field describes him as “the most uncomplicated horse” she has ever re-started, and she was soon taking him to hunter paces and even a schooling show.

“For two years, things were awesome,” Field said with a laugh. “Everything was so easy.”

That all changed one October morning in 2016, when Field went to feed and found Holden caked in mud, covered in lacerations embedded with rocks, and barely able to move.

Mystery Injuries

She still doesn’t know exactly what happened to Holden, who had been living on 24/7 turnout at her mother Khristine Field’s Seven Acre Farm in Littleton, Massachusetts. She called Dr. Brett Gaby, DVM, of Essex Equine, who made it to the farm in less than 20 minutes.

“As my vet put it, the mud and lacerations suggested he had some sort of catastrophic encounter with the ground,” Lauren said. “It is so rocky here; our best guess is he fell on some ledge.”

Gaby began the painstaking process of removing rocks and pebbles from Holden’s many wounds, most of which were located along his left shoulder, rib cage and hip. One puncture wound was so deep Gaby was concerned about involvement with the cecum, which is part of the large intestine, and they discussed sending Holden to the equine emergency hospital at Cummings School of Veterinary Medicine at Tufts University in North Grafton. But even with pain medicine on board, Holden wouldn’t move.

“He has never said no to me my entire time having him, and I could not get him into the trailer,” Lauren said. “He wouldn’t walk.”

Holden’s behavior, combined with a massive hematoma covering his left hindquarter, which stretched from the last rib to the gaskin, made Gaby suspicious the horse may have suffered significant internal injuries. In particular, he worried about a pelvic fracture. But given the degree of inflammation, he felt imaging in the field would likely prove inconclusive. Lauren began to consider euthanasia, but Gaby encouraged her to give the horse a chance.

“He was like, ‘We are not there yet; let’s see how he navigates the next couple of days,’ ” Lauren said.

Lauren set up a medical stall for Holden, and for the next three weeks, Gaby and his technician visited several times a day to administer pain medication and anti-inflammatories, and to monitor Holden’s overall well-being.

“Their commitment to his welfare was above and beyond,” Lauren said. “I owe them my horse’s life.”

As the days progressed, the gelding showed no sign of intestinal damage, and once the inflammation began to subside, almost three months later Gaby was able to use x-ray and ultrasound to better evaluate the extent of Holden’s injuries. Imaging revealed the gelding had fractured his pelvis in three different places—the acetabular rim, the ilial shaft and the tuber coxae, which was splintered into multiple bony fragments. Additionally, he had three broken ribs. The diagnostics also revealed that Holden had a mild case of kissing spines and some neck arthritis.

“There were so many things going on with this horse,” Lauren said. “My vet said not many horses come back from a pelvic break, and he was probably going to be a pasture pet. I said that’s fine—he has a stall with us for the rest of his life—but I asked if I should consider putting him down. It’s a pretty significant injury.”

Again, Gaby encouraged Lauren to give Holden more time. The gelding, though not initially thrilled to be confined to a medical stall, had never gone off his feed, and his vitals were stable. He seemed to be demonstrating the same toughness that had gotten him through his track injury. With her veterinarian’s support, Lauren decided to pursue a conservative course of treatment: rest.

“We just had to wait and see if he got better—and he did,” Lauren said, her voice catching.

‘I Didn’t Want To Push Him’

In late spring 2017, Gaby cleared Holden to return to ridden work via a slow, progressive 12-week conditioning program. When the gelding handled that well, Lauren spent the next year working almost exclusively at the walk and trot, mostly hacking out or doing ground pole work to strengthen his body. She joined Facebook groups to learn new exercises intended to support horses with kissing spines or hip injuries, and she peppered her vet with questions.

“I didn’t want to push him; he’s way too generous a horse, and he would say yes, even if he was hurting,” Lauren said. “I was very mindful of that.

“My vet was thankfully phenomenal the entire time, navigating me through putting him back to work,” she continued. “Dr. Gaby was amazed—floored—by his recovery, and said that Holden will tell me if it’s too much.”

Despite the support she received, Lauren admitted she still struggled with self-doubt when it came to deciding when and how much to ask of Holden.

“I am hypercritical of horses’ soundness, and I kept texting my vet little video clips: ‘Is he sound? Do I keep asking for more?’ ” she said. “There was one point early on when we began trotting, where I didn’t like how he looked, so I went back to the walk. That was part of the reason it took so long to get him back to where he was before—I wasn’t willing to work through something I felt was an unsoundness.”

Ultimately, it was the horse himself who convinced her.

“Holden always came up to me in the paddock, always with a, ‘What are we doing? When are you taking me out?’ type of attitude,” she said. “They will tell you, through their facial expressions, through their body language. He just hasn’t said no yet. I have to be careful, because he’s not the type to say no. My mom will tell you it is me babying him, but I have to honor him, too.”

Back To Business

In April 2018, not long after Holden had resumed jumping, Lauren underwent knee surgery that kept her out of the saddle for several months. While she recuperated, Holden enjoyed additional time off. But that July, he was the first horse she sat on post-surgery.

“That is one of the things that is incredible about his personality,” she said. “I can put him on the back burner, then get back on him, and it’s like nothing happened. He’s not frisky; he’s not rude. He’s unfailingly polite.”

In addition to riding plenty of hills and doing pole work to keep him strong and supple, Lauren found that 24/7 turnout, four shoes and twice yearly mesotherapy injections best work to manage Holden’s kissing spines. These practices also support his pelvis.

For the next several years, Lauren and Holden focused on hunter paces and training, with an occasional unrecognized competition on their calendar. But in 2023, Lauren became an adult member of the Groton Pony Club, which she describes as “transformative.” With the encouragement of other members, that June, she entered her first USEA-recognized event in over a decade, beginner novice at the Green Mountain Horse Association in South Woodstock, Vermont.

“I’d avoided recognized events because they are so much more costly here than unrecognized,” Lauren said. “I would rather put my money toward his mesotherapy and massage. But I was given an event voucher by Muffy Flynn, another eventer, which was so generous.”

However, after a steady dressage test and a solid stadium course, Lauren thought Holden didn’t feel like himself out on cross-country, and she pulled up. In hindsight, she believes the long trailer ride and multiple nights in stabling had taken their toll on his body.

“I felt so bad disappointing all these people that had come together to make the event happen for us, but I felt I owed it to Holden to listen to him,” she said. “He wasn’t supposed to come back from this, and he doesn’t owe us anything, after everything he’s been through.”

‘Absolutely Not’—In A Good Way

After concentrating on schooling for the rest of the season, in 2024, Lauren felt Holden was ready to tackle another recognized event, this time the June Apple Knoll Horse Trials (Massachusetts). Not only was the venue nearby, but the Central New England Region Pony Club eventing rally was held in conjunction with the competition, meaning she could represent her club as well.

“It was an enormous undertaking to be doing a rally and a recognized event at the same time,” she said. “I remember pulling into the parking lot and thinking, ‘What did I sign myself up for?’ ”

It poured during their dressage test, causing Lauren to lose focus and make a mistake, but she was able to set that aside for a “fantastic” and clear stadium round, before heading to cross-country. With the day’s rain, she knew footing would be boggy and was prepared to pull up at any point.

“He jumped everything ears forward,” she said. “Toward the end of the course, he pulled a shoe. I heard it go whizzing by me. I started to pull him up, but Holden said absolutely not. He had seen the last three fences; they were all in a line, and he just carried me over them. It was incredible.

“I finally finished my first recognized event in 10 years,” she continued. “It was such a victory for me, but it was also such a victory for him, because he had been through so much. Life has knocked him around a lot, and he still has this unflappable attitude where he shows up every single day at the gate like, ‘What do you have in store?’ ”

Lauren looks forward to many more years with her favorite Thoroughbred, and possibly a move up to novice in eventing. When she has time, Lauren is also producing a young Hanoverian named Evie, whom she hopes might help her pursue national level Pony Club certifications, allowing Holden to enjoy a more leisurely pace of life.

“I’m taking it one day at a time, because I think if I put too many expectations on him, it might not be ethical or fair,” Lauren said. “He is the perfect amateur horse. He’s there for me; I can ride him, and he says yes to anything I ask. He is so honest. For me, he is the textbook Thoroughbred, and every single day with him is a blessing.”

Do you know a horse or rider who returned to the competition ring after what should have been a life-threatening or career-ending injury or illness? Email Kimberly at kloushin@coth.com with their story.

The post A Broken Pelvis And An Unexpected Diagnosis Don’t Stop OTTB Eventer appeared first on The Chronicle of the Horse.

]]>The post Back From The Brink: An Amputation Can’t Keep Andrew Diemer Out Of The Tack appeared first on The Chronicle of the Horse.

]]>“You can’t keep me away from the barn for too long,” he said with a laugh. “And I wouldn’t want to be.”

Born with a bicuspid aortic valve—his heart had only two flaps instead of three regulating the outward flow of blood—Diemer was at a higher risk of contracting infections involving the heart. But beyond being prohibited from playing full-contact sports like football, the condition had never slowed Diemer down or prevented him from doing what he wanted to do.

That all changed in 2014, when a series of atypical symptoms culminated in a diagnosis of endocarditis, a rare but life-threatening infection causing inflammation of the heart’s inner lining and valves. In the quest to save his life, Diemer would ultimately undergo a series of open-heart surgeries and lose part of his right leg. But true to his past, Diemer didn’t let even these major health issues keep him out of the tack for long.

Watching Diemer ride today, whether in the jumper ring or on cross-country, you wouldn’t necessarily notice he wears a prosthetic on one leg—except for the time when, according to his mother Dana Diemer, he left the polocrosse field calling for an Allen wrench because “his foot had come loose and turned around.”

Trying Every Sport On Offer

After getting his start foxhunting in New England, Andrew rode with several clubs around the country, as his military family moved regularly; at 6, he earned his junior colors with the South Creek Foxhounds in Tampa Bay, Florida. In 1997, the Diemers settled in North Carolina, where Andrew joined the Moore County Pony Club and began to explore other equestrian disciplines. In what he calls “traditional young boy fashion,” he tried every sport on offer within his first year.

“I developed an affinity for eventing, because, of course, you have the adrenaline of cross-country,” he said. “But largely, for much of my early career, I was sort of your stereotypical young boy. I was pretty good at the jumping, and pretty terrible at the dressage. And as far as Pony Club went, when it came to keeping myself clean—well, my horses were always well tended, but at formals, I was often the kid who had dirt on his breeches.”

Andrew and his father Manny were first exposed to polocrosse through U.S. Pony Clubs; Andrew describes the sport as a cross between polo and “father-son go out back to toss the baseball.”

“What’s great about polocrosse, unlike many other horse sports, is that it is a true team sport,” Andrew said. “Eventing, show jumping or dressage can be team sports, but you are never in there with your teammates at the same time. They are individual sports, where you compile the scores.”

Both Andrew and his father were excited to bring polocrosse back to their local Pony Club—the organization’s first polocrosse rally was held at the Diemers’ leased farm—and they also became some of the first North Carolina-based members of the American Polocrosse Association.

“Polocrosse is still a very small sport in the U.S.,” said Andrew, who noted it is most popular in Texas and Wyoming. “Which means if you show any form of talent, you don’t have as much competition for [international] teams.”

That is perhaps Andrew’s modest way of acknowledging that, by age 16, he was invited to represent the U.S. in international tournaments, making several trips to play in Australia. At 17, he was part of a group of 20 American polocrosse athletes to spend a month training and playing in South Africa. Andrew admits he made it to his C-2 certification in Pony Club expressly to be eligible to represent the organization in a polocrosse exhibition held in the United Kingdom in conjunction with the 2011 World Cup.

Andrew eventually played polocrosse at the “A” grade level, which he equates to advanced in eventing. In 2013, riding his Australian Stock Horse mare Keystone Silhouette, Andrew was part of the first—and perhaps only—non-Texas-based “A” grade team to ever win an American Polocrosse Association national championship. “Stella” was named best conditioned horse.

“That year, the nationals were held here, in Pinehurst [North Carolina], so it came with all the added emotion of winning on home soil,” Andrew said. “I am very proud of that. But as much as I loved polocrosse, because it is such a small sport, you can’t really be a polocrosse professional. As far as a professional sport, I was going down the road of eventing.”

Andrew had always pursued his eventing goals alongside his polocrosse game, and a Canadian Sport Horse gelding named Cold Harbor eventually brought him to the intermediate level. Under the tutelage of Holly Hudspeth, the pair qualified for the 2008 Young Rider Championships (Colorado) at the two-star level, finishing ninth individually and second in the team competition.

From Joint Pain To Amputation

By 2014, Andrew was 24 and living in Maryland, working an assortment of jobs to make ends meet while riding. When he started experiencing joint pain that fall, Andrew’s doctors assumed he had contracted Lyme disease, because his outdoor-based lifestyle meant he was constantly exposed to ticks. He was put on a course of doxycycline, a powerful broad-spectrum antibiotic known for being effective against the disease’s causative agent.

“The doxy seemed to be tamping down the symptoms, but it wasn’t stopping anything,” Andrew recalled. “And then, I started developing a fever on a regular basis.”

This additional symptom, combined with the mediocre response to doxycycline, led to a rheumatoid arthritis diagnosis. He wasn’t convinced; no one in his family had a history with the autoimmune disease, and he had no other symptoms. But he started taking the prescribed immunosuppressant anyway—with disastrous results.

Two weeks later, Andrew woke up coughing so badly he vomited. Soon, he could barely breathe, and his fingernails had turned blue. He texted his then-girlfriend, who left work immediately to take him to the local emergency room.

“When my immune system was already fighting what would later be revealed to be a severe bacterial infection, having my white cells have their legs come out from underneath them was not what needed to happen,” he said. “Pun totally intended.

“By the time I got to the ER, they realized I was going into cardiac arrest,” he continued. “My aortic valve was already rotted away, and my mitral valve was on the way out. The bacteria had been sitting on my heart valves and fighting against my immune system. When the immune system was no longer there because of the medication, it just went haywire.”

Andrew was transferred to the Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, where he was immediately rushed into surgery. Ultimately, he underwent five open-heart procedures to repair the damage, replace his valves and install a pacemaker. But further complications followed.

“One of the concerns with this kind of infection is if the bacteria doesn’t all come out with the surgery—if it gets into the bloodstream—it can cause clots,” he explained. “That’s what ended up happening to me, in two places.”

The first, and most obvious, clot impeded circulation to Andrew’s right foot; the second was more subtle, affecting his left thumb. With little blood reaching the front half of his foot, Andrew underwent a thrombectomy, in which doctors attempted to remove the clot surgically. When the procedure was unsuccessful, Andrew and his medical team arrived at a difficult crossroads.

“I needed to think about my overall health. I realized I can, as brutal as it sounds, lose a foot. But I couldn’t have any more heart problems.”

Andrew Diemer